It’s a wake-up call to look beyond what’s obvious.

Take a second look; things aren’t as they appear.

If we think of life as a grand play, then the city becomes its most dynamic stage, filled with endless possibilities for action and drama. Danish architect Jan Gehl sees cities through the lens of human experience. He looks at how people feel and interact when they are a part of the bustling urban environment. This concept echoes ideas from symbolic interactionism — a way of thinking about how we engage with our surroundings. Cities are like intricate visuals that we see but don’t fully understand. Underneath the exterior that we easily recognize lies a hidden layer, a kind of “dark side” that we feel but don’t often think about.

So, what mysteries lie on the flip side of the urban fabric? What lurks inside hallways, rooms, and corridors that serve as mere backdrops in our daily lives?

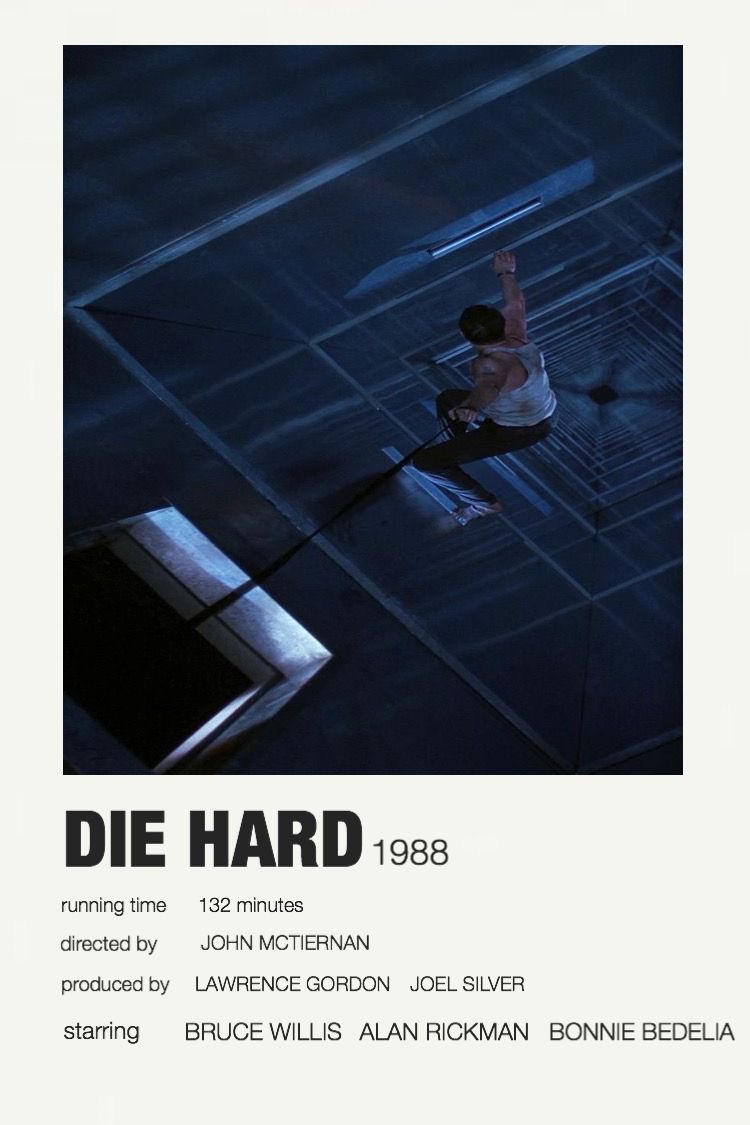

The quintessential ’80s blockbuster, ‘Die Hard,’ beneath its adrenaline-fueled exterior, engages in a nuanced dialogue with the hidden spaces of architectural landscapes.

Two Movies, One Theme: unveiling Hidden Spaces

On the surface, it looks like a typical action film from the 1980s. But when you dive deeper, you realize it offers a powerful look at architectural spaces — those staff rooms and ventilation corridors we don’t usually think about. While watching the film, I felt a sense of tightness or claustrophobia, especially when the focus was on the towering Nakatomi Plaza building. This building not only appears overwhelming but also represents a specific urban phenomenon called “Manhattanism.” This term, coined by architect Rem Koolhaas, means that city spaces are always being “disentangled” and “reassembled’ in new ways — through things like elevators, tall buildings, and even underground tunnels.

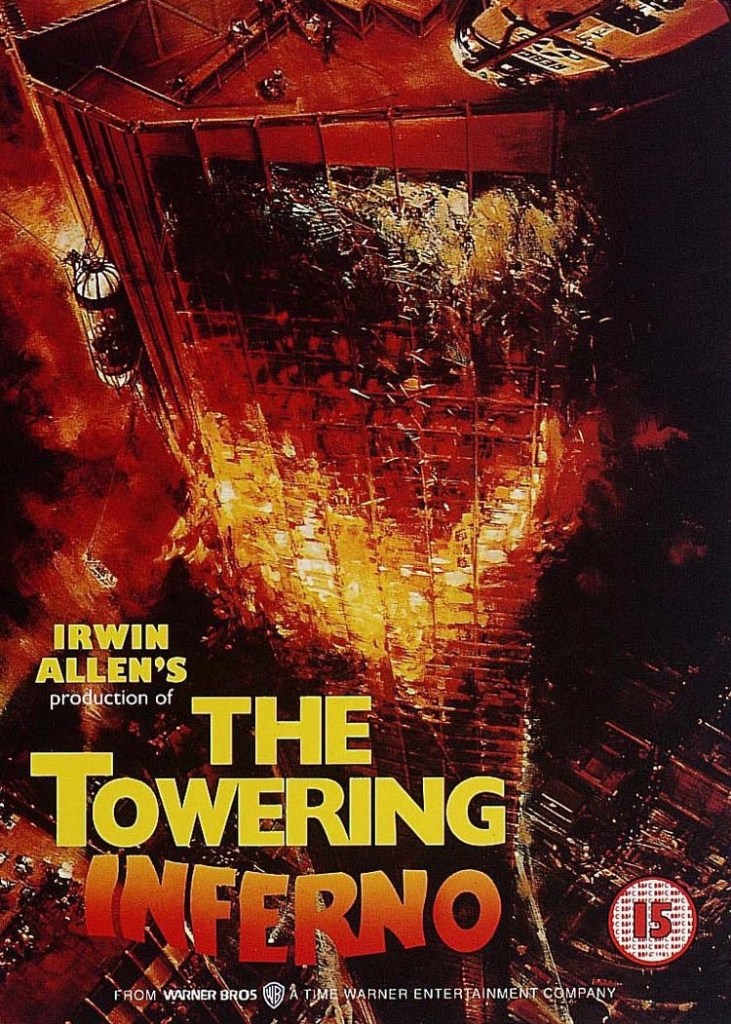

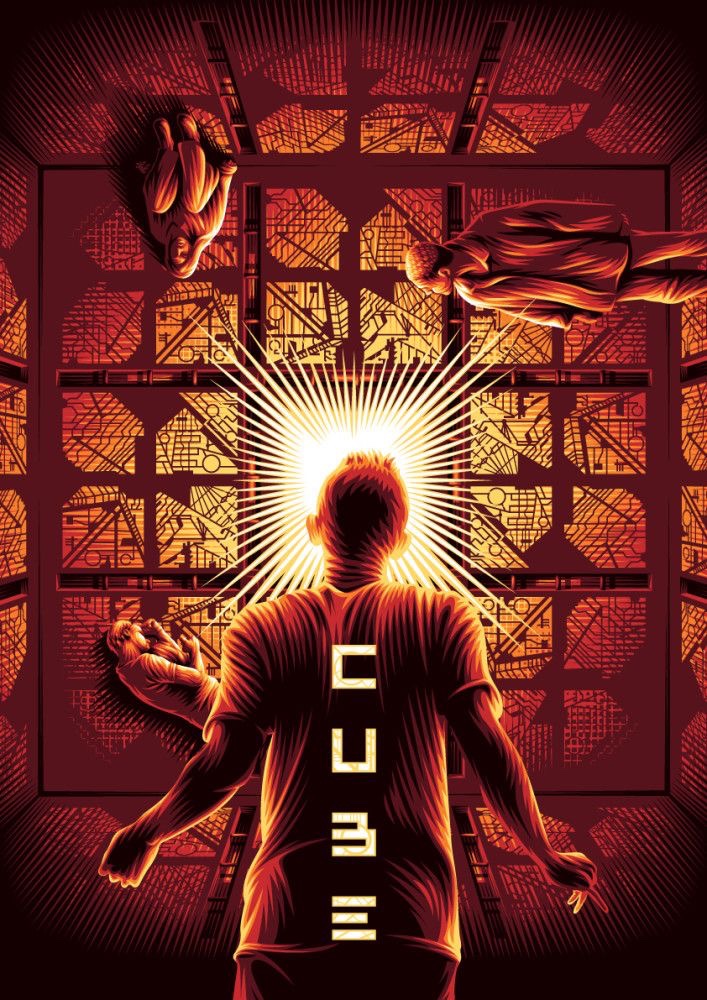

Remarkably, the mainstream cinema firstly began to portray skyscrapers as isolated glass cubes in the post-1960s. The 1974 film ‘The Towering Inferno’ features The Glass Tower, an inhumanly towering structure that encapsulates this aesthetic shift. Fast forward to the 1990s, and this grim portrayal is perpetuated in the horror-thriller ‘Cube,’ a film steeped in a disturbing sense of isolation and despair within a deadly glass labyrinth.

But even though movies like ‘Die Hard’ offer such compelling looks at architecture, they often miss out on exploring the emotional side. The sensation of being confined or trapped — feelings of sticky anxiety or claustrophobia — aren’t deeply examined. Instead, these films usually follow a predictable scenario of the Hero’s Journey.

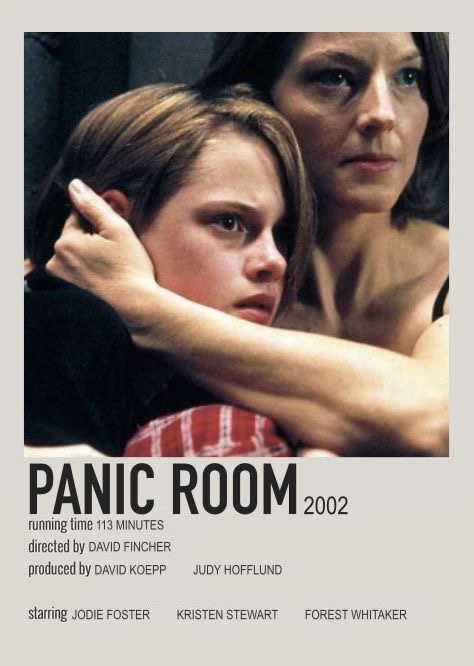

In contrast, another movie called ‘Panic Room‘ tackles this head-on. In this suspenseful film, characters hide from intruders in a secret room. The experience is far from heroic; it’s actually a terrifying form of confinement that leaves them gasping for air.

Breaking the Rules: How ‘Die Hard’ Flips the Script

In ‘Die Hard,’ Bruce Willis’s character, John McClane, navigates the Nakatomi Plaza in an unconventional way. He doesn’t use stairs or doors. Instead, he maneuvers through the obstacles in the form of narrow ducts, elevator shafts, trapdoors, pipes, and other maze-like spaces. By doing this, he flips our normal understanding of the building inside out. According to some analyses, like one by Sharon Willis in her book ‘High Contrast: Race and Gender in Contemporary Hollywood Films,’ since those spaces are hidden from our sight, the building becomes a kind of prison that seems impossible to escape. But McClane challenges this view by using the building’s hidden pathways to his advantage, turning the skyscraper into both a weapon and a safe haven. Geoff Manaugh compares McClane’s “inside-out movement” to the Israeli troops’ movements through the tunnels inside buildings.

Seeing Beyond the Surface

What ‘Die Hard’ accomplishes is more than just action-packed entertainment; it opens our eyes to the hidden aspects of the urban spaces we inhabit. The movie urges us to rethink our cities — not just as collections of rooms and buildings but as complex networks of unseen pathways. It’s a wake-up call to look beyond what’s obvious. Take a second look; things aren’t as they appear.

Sign up for our freshly baked posts

Get the latest culture, movie, and urban life updates sent to your inbox.

Subscribe

Join a bunch of happy subscribers!

You must be logged in to post a comment.