The French… adore ‘Gone with the Wind’, but they don’t see why Hollywood would become an issue if they want to make a film about their girlfriend and the Elysian fields.

Jean-Luc Godard

The innovativeness of the Italian and French New Wave filmmakers was classified by André Bazin based on the concept of forbidden montage, the theme of a Kafkaesque-driven little man, long static pans, and everything else that was entirely unlike conventional filmmaking. New Wave films feature a scenario of pure observation, with non-narrative and non-plot-forming aspects dominating, an uncertain lacunarity in narration, and a reduction in events and temporal features. Acting heroes do not exist, and heroes can have no real purpose. The common protagonist in these movies is the roaming hero of Gilles Deleuze or Baudelaire’s flâneur, the hero-observer. In other words, the New Wave rejects the use of cinematic montage to invent reality, as Eisenstein’s film did, and instead aims to capture it as faithfully as possible through a continuous stream of life.

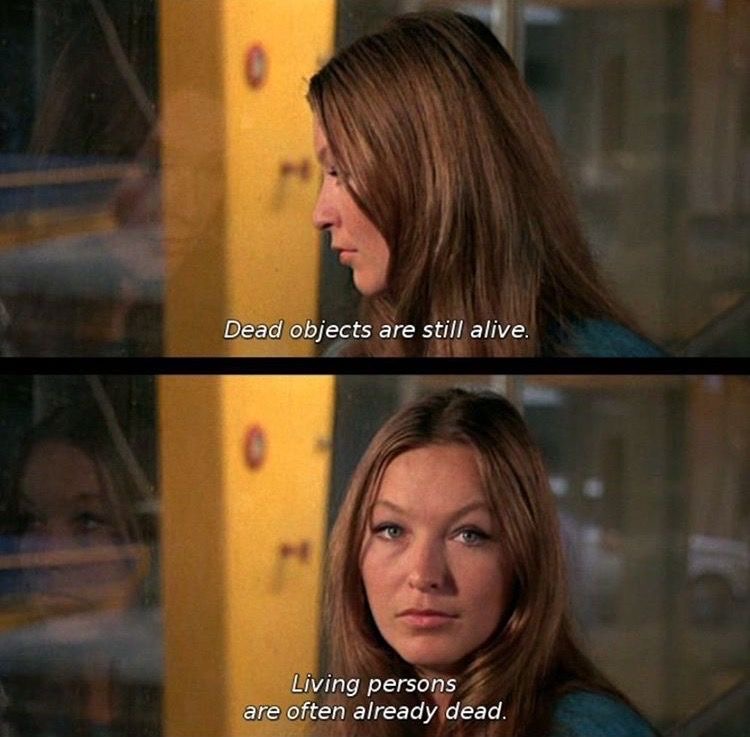

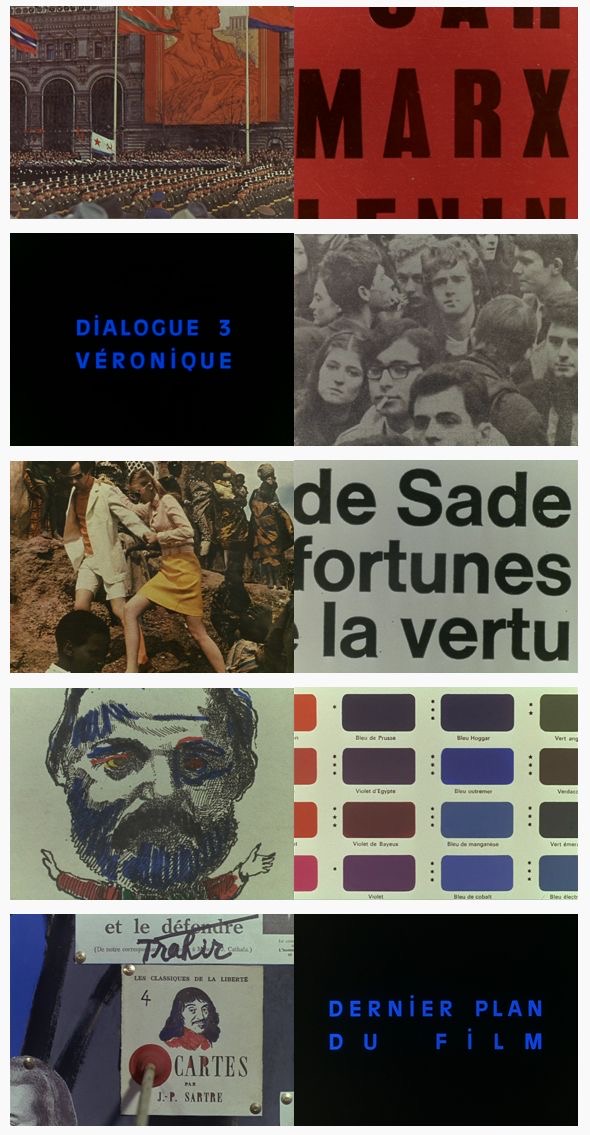

The dialogues and “thoughts out loud” of the heroines, similar to internal monologues, seem random. There is no clear plot or established cast of characters. Sound and image are frequently out of sync or superimposed, and the narrator’s voice is heard off-screen ruminating on abstract subjects (such as what constitutes an object, whether an object is an object; there is even a quasi Baudrillard’s conversation about hyperreality).

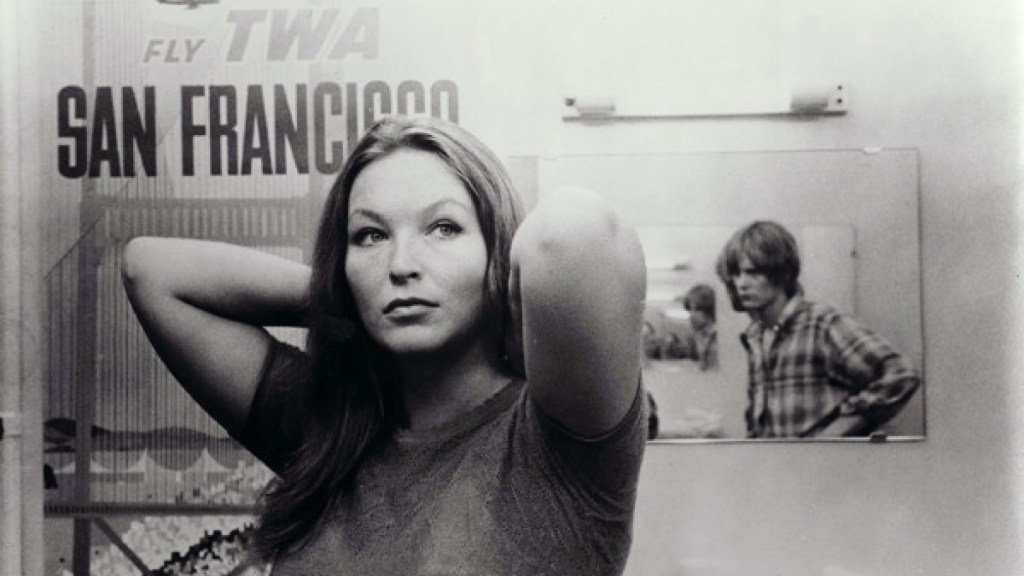

To discuss Godard’s film Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), all of this extensive preamble is necessary.

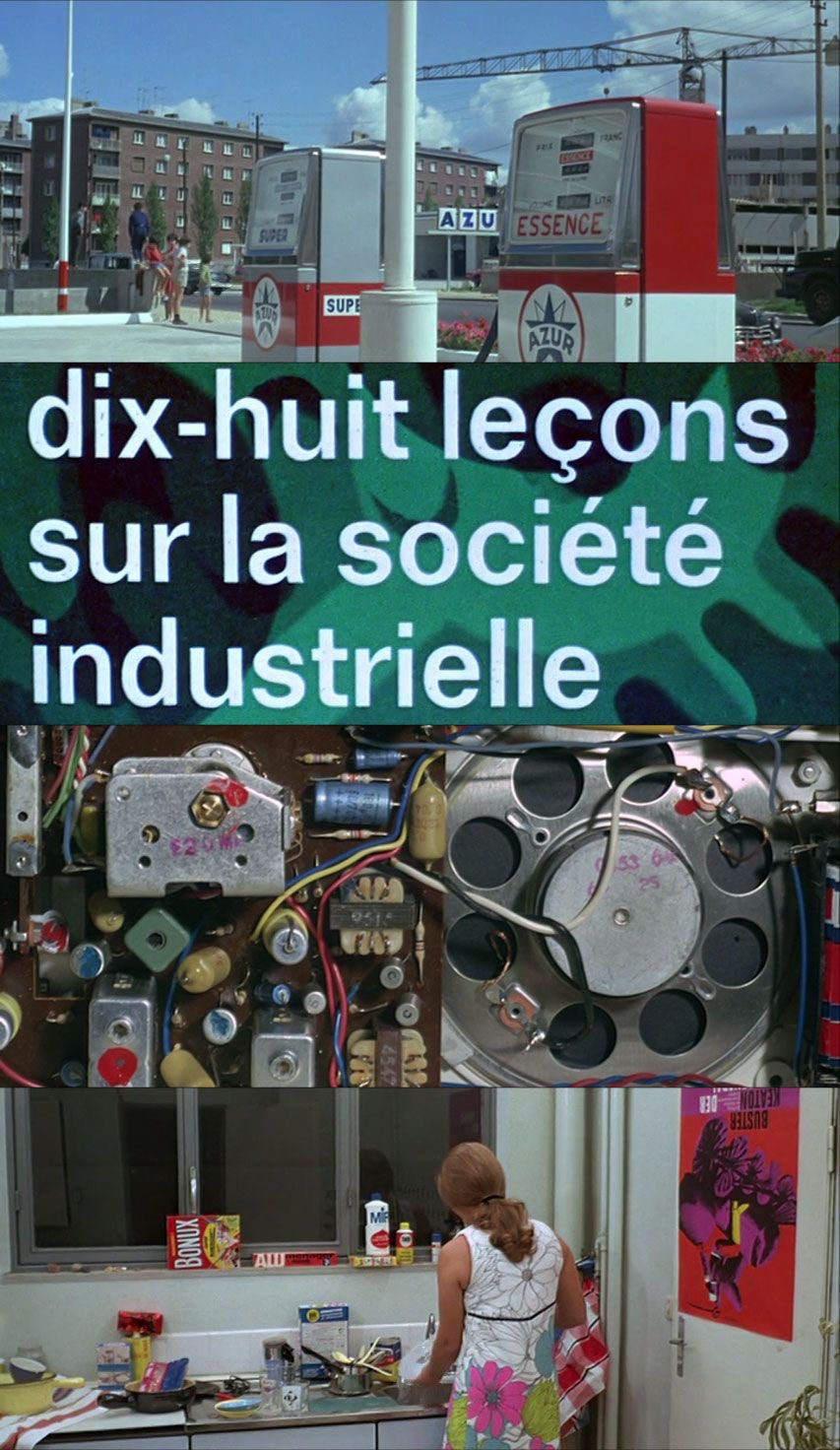

The film’s structure explicitly embodies Godard’s notion of politically constructed films: it is based on the narrator-director’s own memories of Paris in the 1960s. The narrator’s off-screen intonational intimate comments are perceived as a personal diary and uncover urgent social and political issues of the day, including his lingering doubts about many cultural processes (expanding consumerism, depersonalization, and unemployment practices that drive wealthy girls from Paris’ elite neighborhood into prostitution ) and a strained military situation (the war in Vietnam). Excerpts from low-quality sociological journals and episodes or events appear to split the movie into subchapters, using discreet editing.

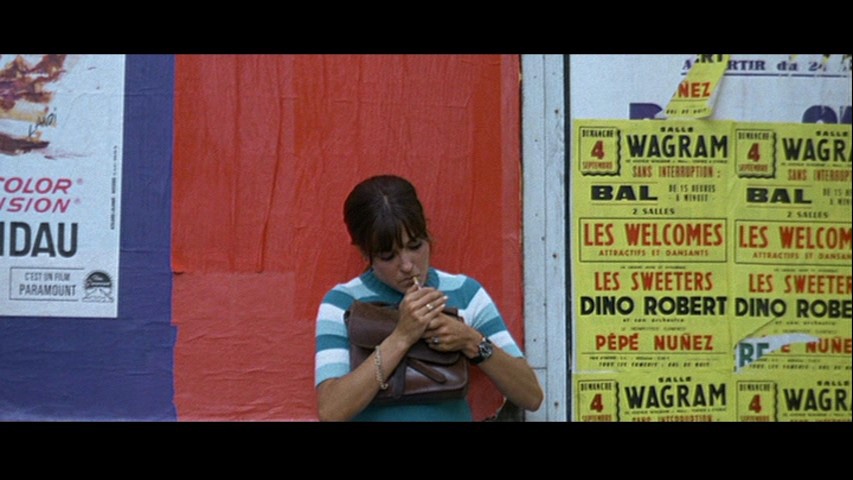

All of this is laboriously diluted by chaotic modernistic and static checkpoints. Everything is recorded like a photograph since the camera is practically never moving and there are never any dynamic angles. Here, we recall Deleuze, who viewed the city as an escape from artificiality, improvisation, spontaneity, and cacophony in this film. Godard uses the metropolis as a metaphor for endless consumerism as well as what he refers to as the prostitution of consciousness.

The continual mixing of vibrant contrasting hues shows that this method is being purposefully juxtaposed with the acute urbanization of the frame (red-blue, red-white).

Finally, a film-resistance emerges, displaying the characteristic Godardian meta-reflection on the reality of cinema. Making politically charged films is crucial to Godard. This implies that the political content of the movie shapes its own cinematic language, including its editing, color and sound design. Yet the theme of the movie, resistance, also has something to do with national identity. The optics of national self-expression of Renan influence Godard’s interpretation of the cinematographic movement: The French… adore ‘Gone with the Wind,’ but they do not see why Hollywood would become an issue to them if they want to make a film about their girlfriend and the Elysian fields.

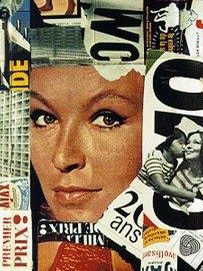

Visual Assamblage

If you are eager to listen to an in-depth analysis of Godard’s visuality, follow the link:

Sign up for our freshly baked posts

Get the latest culture, movie, and urban life updates sent to your inbox.

Subscribe

Join a bunch of happy subscribers!

You must be logged in to post a comment.