Urban What-Being and All That Jazz

Sunday Edition

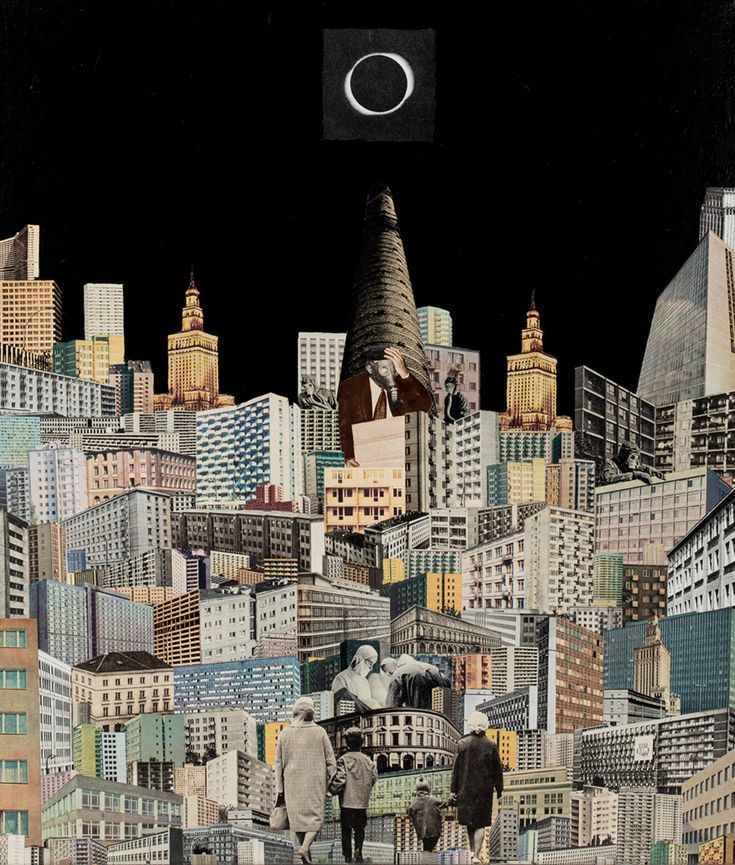

We’re back with another exploration from the margins — one of those moody Sundays when the city feels like a skin too tight. Let’s talk about all the things that bruise beneath concrete: memory, drift, prefab architecture, and the unresolved trauma of a geography that still doesn’t know its name.

“Time-Lapse”, Christopher Street, West Village, NYC by Xan Padron

a psychogeographic remix of urban drift, panel nostalgia, and the phantom limb of the New East

What does it mean to exist in a city? Not just survive traffic and scroll real estate horror reels on Instagram, but to actually feel the city’s weight pressing into your bones? Welcome to today’s entry—a medley of urban theory, psychogeography, and existential nausea. Think of this post as a dérive through broken sidewalks, brutalist monoliths, and the haunted memory of a Soviet stairwell.

Let’s start with some philosophy, shall we?

I. URBAN DRIFT, OR THE ART OF GETTING LOST ON PURPOSE

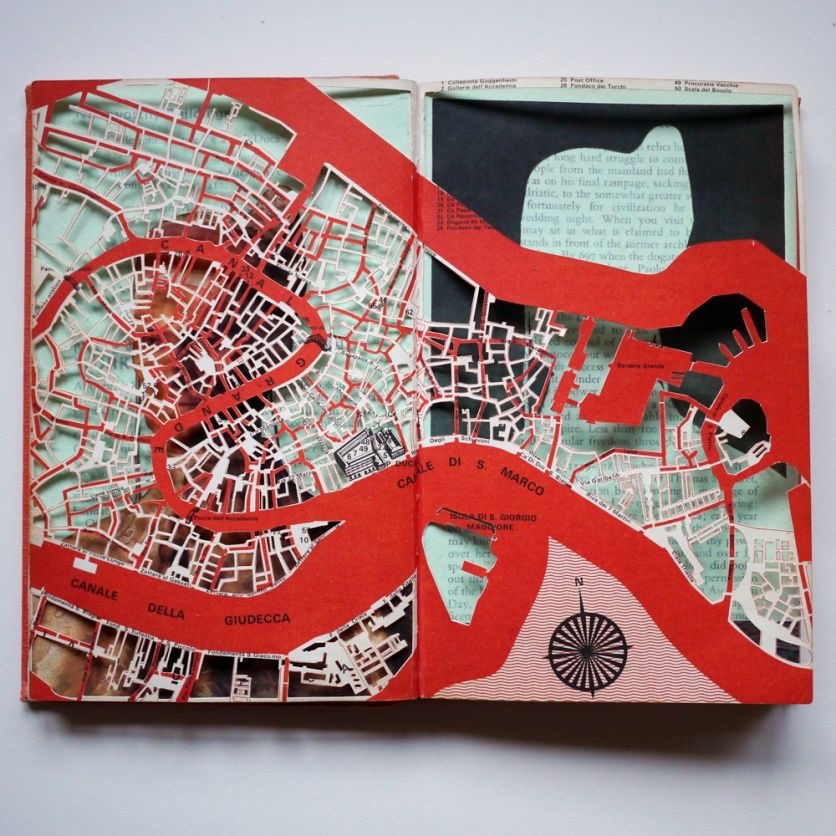

Psychogeography — Guy Debord’s term for the dérive, the drift — isn’t just a flaneur’s game anymore. It’s a political act. It’s what happens when walking becomes method, when space turns symbolic, and when the city talks back. Drifting through familiar streets allows one to see not a map, but a palimpsest of memories, moods, and emotional cartographies.

Debord spoke of the city not as space but as emotional texture. Urban flow becomes performance. The concrete becomes corporeal. And it’s precisely this mode of knowing—the everyday reenacted—that leads us to what urban theorists call “urban being-here-now.”

But really, it’s about drifting—letting the city guide you instead of sticking to the app. Walking as resistance. Walking as narrative. Walking as existential critique. To wander without purpose is to disassemble the city’s capitalist logic — the logic of flow, destination, surveillance, and consumption. Walking, as Michel de Certeau said, is already writing. The dérive? A kind of storytelling. Think of it as a mesh of presence, estrangement, and dread. A kind of Sunday melancholy that tastes like unfinished Soviet plaster.

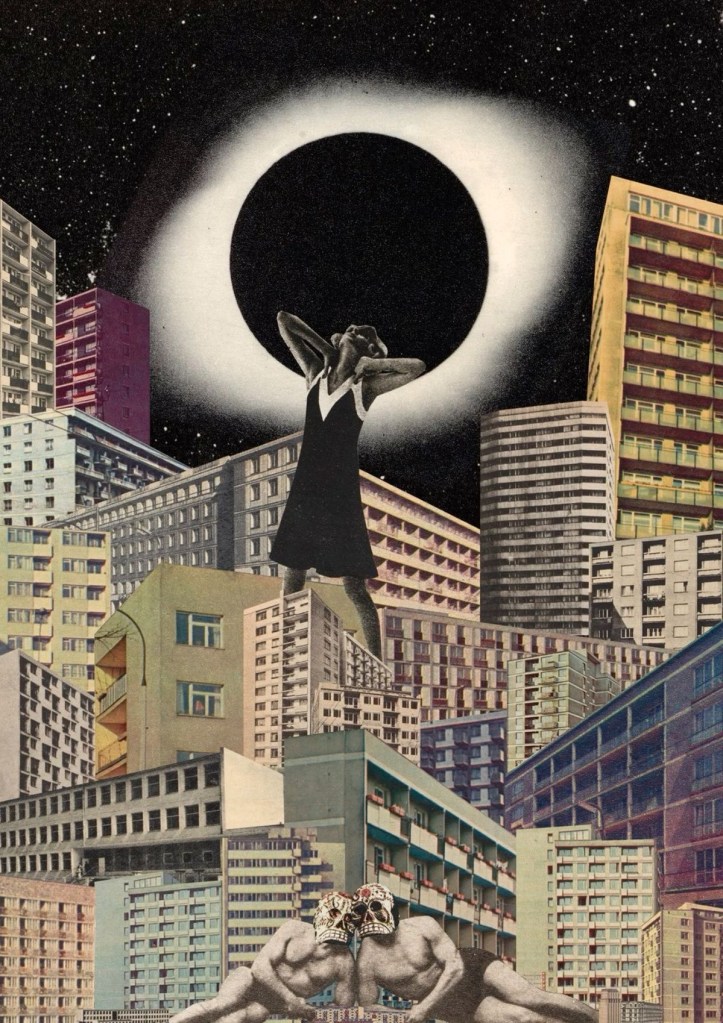

II. THE INVISIBLE CITY: ANXIETY AND ITS ZIP CODE

As Strelka Press’s anthology “The Citizen” points out, the city’s most disturbing quality is its presence of otherness. The foreign next to the familiar. The uncanny in the everyday. Fear in the city arises not from the unknown, but from what’s almost too known—“the bad neighborhood,” “the broken escalator,” “the one building where the lights are always off.” The moment a city reveals its festering edges, it’s no longer just infrastructure. It’s sentient. It’s watching you back.

Scott McQuire calls poor neighborhoods “invisible,” and what’s invisible scares us most. Like monsters under the bed. Only the bed is now a five-story Khrushchyovka. And the monster is gentrification in soft focus. Facing urban fear means seeing its abscesses.

Want to test the theory? Walk alone through a dark park at night. Now imagine city policy-makers asking: why not just install lights? Why not let women walk without keys clenched like weapons?

III. PANELKA: MASS HOUSING, MASS MEMORY, MASS AMNESIA

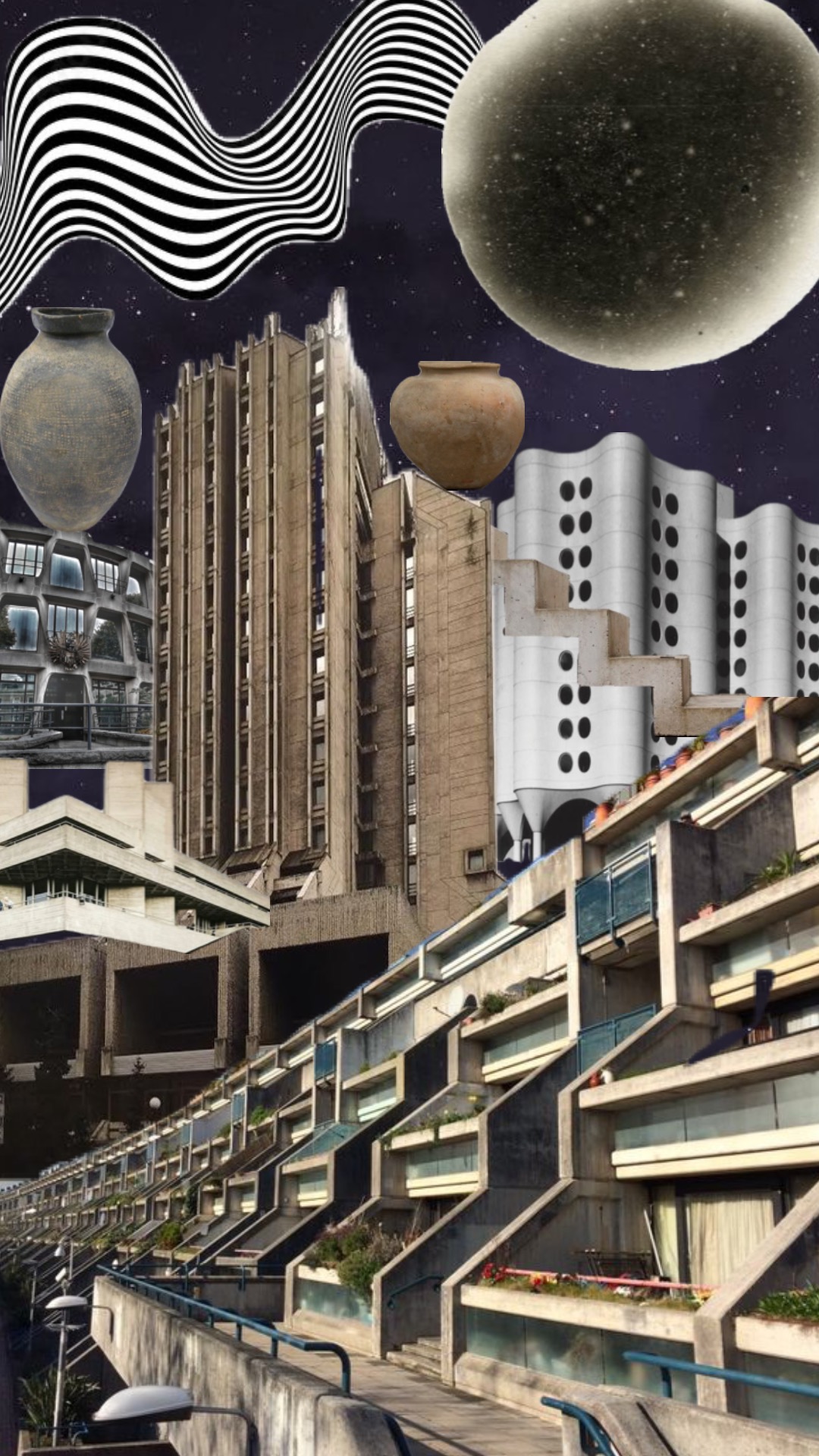

Let’s talk concrete — literally. The Soviet-era panelka (prefabricated panel housing) once symbolized utopian egalitarianism and now flickers between dystopian meme and retro-chic icon.

According to Emma Tarasenko’s deep dive on panel housing in SHER, the panelka wasn’t born in the USSR but owes much to early 20th-century ideas of functionalism — from New York’s Forest Hills Gardens to Le Corbusier’s modular utopias. By the 1960s, the USSR adopted the panelka not just as a housing solution, but as a new spatial ideology. The homes were cheap, replicable, scalable — an industrial answer to postwar trauma.

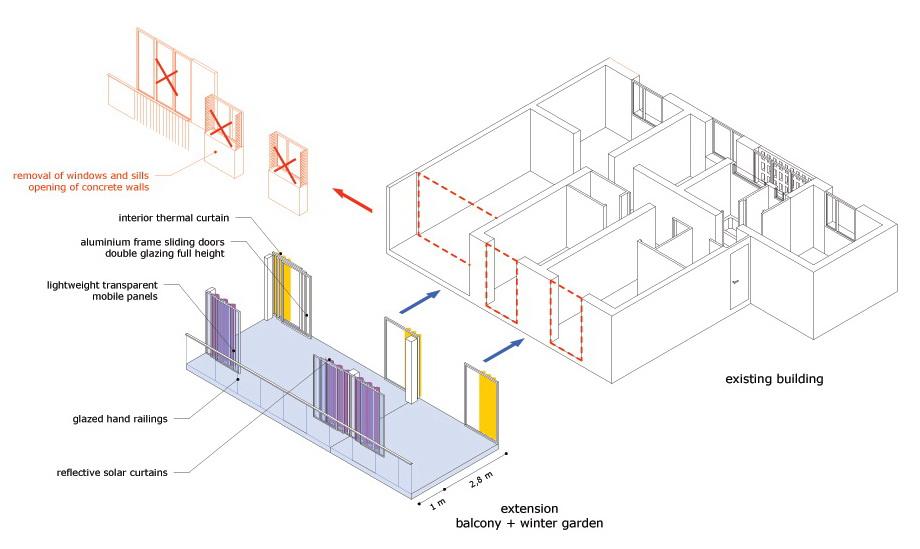

Yet in Europe, as SHER notes, these buildings are undergoing a resurrection. Across Germany, France, Czechia, and Lithuania, façades are being repainted, balconies expanded, green space added. The panelka is not being demolished but re-scripted.

But the dream frayed. As Ich bin Kristina, a memoir set in 1970s Gropiusstadt, recounts: “From afar everything looks new and tidy. Up close — the optimism vanishes.” The anonymity of endless blocks, the erased subjectivity of those who lived there — all of it dissolved into concrete fatigue.

Kevin Lynch would call this a legible city: the act of re-individualizing space makes neighborhoods not just livable, but lovable. Panelka, thus, becomes not past trauma but future potential.

From Urban Fear to Urban Erasure

If you think your city can’t get worse, think again. Moscow’s war on its own architectural memory continues—Hovrino, Khokhlovka, and even Ilya Kabakov’s works are being erased for glassy business clusters:

• The demolition of Solovey cinema

• The war for Khamovniki and Khokhlovka

• The literal destruction of Ilya Kabakov’s social-art relics

• And let’s not even start on the mock-renovation schemes erasing local residents’ agency

Concrete Comes Back

But elsewhere, Soviet heritage is getting a glow-up. While Russian heritage crumbles, Europe gets aesthetic. Amsterdam now recycles 1950–80s housing blocks into chic eco-friendly spaces. Localized architecture for displaced communities. Soviet kitsch meets community care.

Russia tries too—without rooftop gardens, unfortunately. But it tries. Cultural centers are rebranded. No longer just for awkward New Year performances. See this example of architectural (eco)activism in the DK movement.

Communal Nostalgia

Yes, communal flats are back, too. No, they’re not dystopian punishment—unless your roommate steals oat milk. In fact, today’s coliving spaces are marketed as intentional communities (lol), complete with yoga zones and shared Spotify playlists.

IV. PANELÁK IN PRAGUE: WHEN THE FUTURE MOVED IN AND STAYED

Czech panelák culture took its own path. After the Velvet Revolution, many predicted that these prefab neighborhoods would slide into ghettoization. That never happened. Instead, residents formed cooperatives, took over maintenance, secured funds, and developed sophisticated urban planning systems.

Today, these areas house a cross-section of Czech society — except for the wealthiest — and feature thriving businesses, greenery, and civic life. What was meant to collapse became infrastructure for a different kind of modernity.

V. THE “NEW EAST” AND THE MYTH OF THE OTHER

But space is never just physical — it’s representational. According to Moscow Art Magazine, the label “post-Soviet” has aged poorly. The West needed an update, and The Guardian (of all places) coined one: The New East. With the help of The Calvert Journal, the label grew legs — marketing Eastern Europe as sexy, gritty, creative, and broken-in-just-the-right-way.

But what is The New East, really? A discursive fantasy. A term invented not in Kyiv or Vilnius, but in London. It’s exoticization disguised as celebration, a branding mechanism under capitalism’s chic gaze. The aesthetic is “raw,” the people are “resilient,” the vibe is “authentic.” And through it all, the region’s history — of oppression, revolution, contradiction — is either decontextualized or romantically flattened.

As Borysenok and Sosnovskaya argue, the New East is less about geography than about marketable affect. It transforms marginality into lifestyle, discontent into design. It’s post-socialist steampunk for the Western imagination. And yet — it works. Because within the curated chaos, something real still flickers.

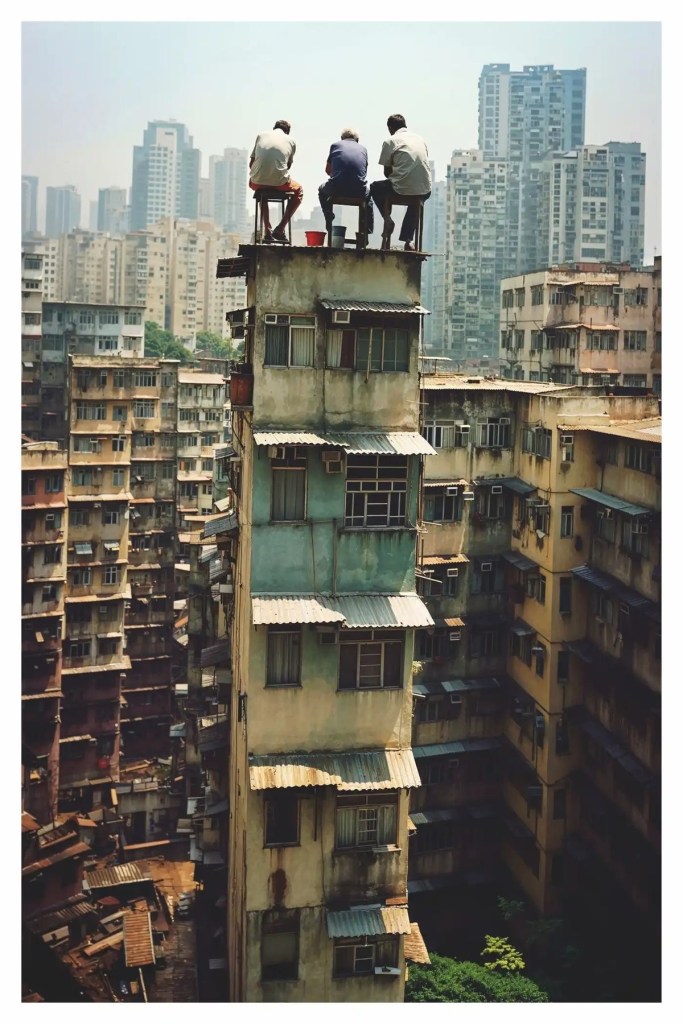

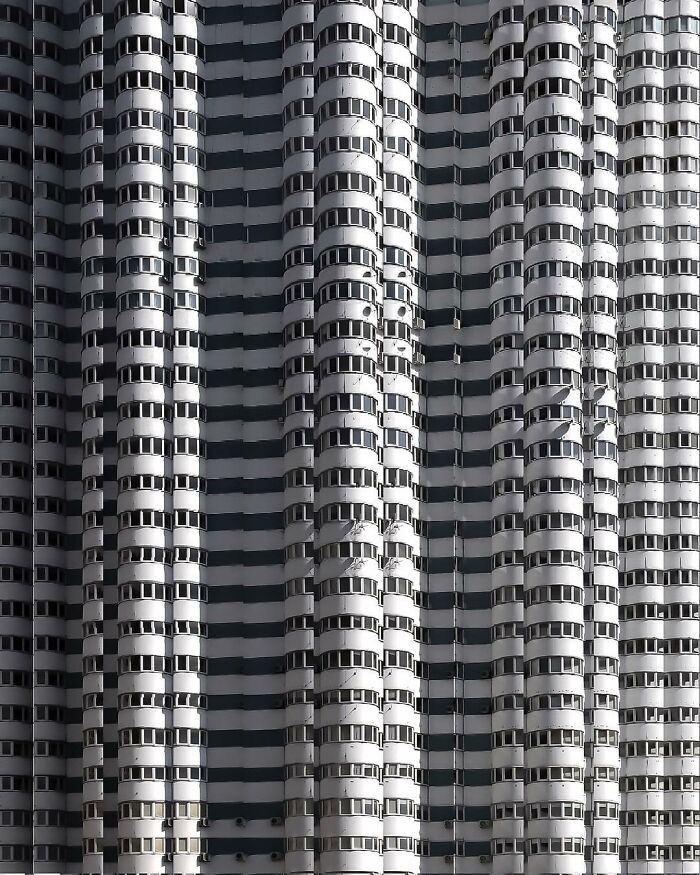

VI. CONCRETE IN MINSK: THE AESTHETICS OF MASSIVE SILENCE

Let’s talk Minsk. The uncanny Brutalist skyline of Minsk—behemoth housing blocks that feel more alien than domestic. Massive, flat-faced, post-Soviet blocks loom like sleeping titans. The horror is not that they exist — but that they’re still here, silent and unchanged, like someone forgot to tell them time moved on. If you haven’t seen them, it’s time to pack and go cityscaping in Minsk.

This is what Svetlana Boym might call “ruinophilia” — the postmodern fetish for the broken, the incomplete, the utopia that never fully assembled.

Need more proof that ghosts live in panelki? Check out PastVu, a crowd-sourced photo archive of urban evolution. It’s like Google Street View with a trauma response.

WE’LL BE BACK:

…with a sinophiliac special next time — on the flesh of film and the embodied turn in cinema. For now, drift responsibly.

Sign up for our freshly baked posts

Get the latest culture, movie, and urban life updates sent to your inbox.

Subscribe

Join a bunch of happy subscribers!

You must be logged in to post a comment.