The Drum, the Deal, and the Double Irony of World Music 2.0

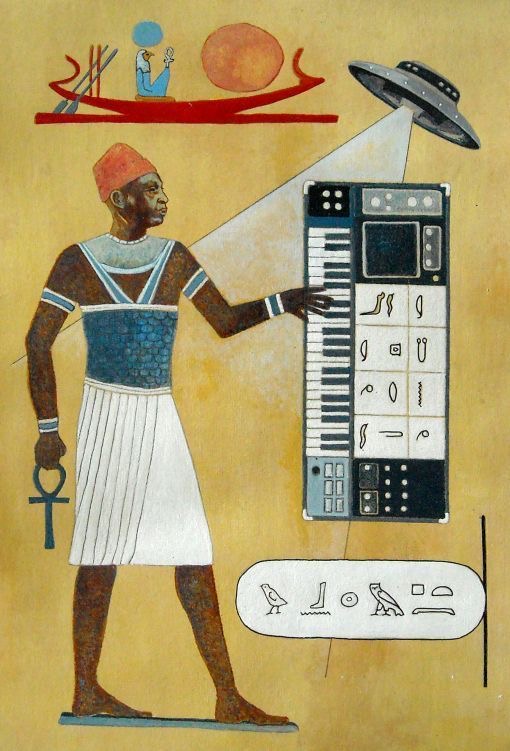

Once upon a time, the world was small enough to be placed neatly on a vinyl record—preferably one printed with palm trees and marketed as authentic. The term world music emerged in the 1960s academic context as a tactful alternative to “ethnic” or “race” music, a soft-serve euphemism meant to sidestep the colonial landmines of classification. Ironically, this gesture toward cultural sensitivity didn’t so much decolonize sound as it rebranded the exotic into something more palatable—romantic Otherness, lightly dusted with ethnographic legitimacy.

But genres don’t descend from heaven. They’re constructed—discursively, commercially, politically—through a slow dance between artists, mediators, and marketing departments. World music is no exception. It’s a genre that was never really a genre—more like a curated moodboard of the Global South for Northern listeners who wanted spice without fire.

Sure, the villainous trope of the greedy studio exec looms large in the narrative. But not all appropriations wear suits. Take Fun-Da-Mental, a British group of South Asian descent in the 1990s, who combined ambient beats with traditional Eastern instrumentation to create what felt like a remix of resistance: a subversive repackaging of radical Otherness in a language familiar to Western clubgoers. Not co-optation, but reinvention—coded for survival.

Or consider Martin Denny’s Exotica (1957), a landmark in the so-called easy listening genre. It offered the middle-class consumer a sanitized safari—jungle sounds without the mosquitos, Polynesia without politics. Ethnic motifs entered the living room, lacquered in stereo, designed to soothe rather than provoke.

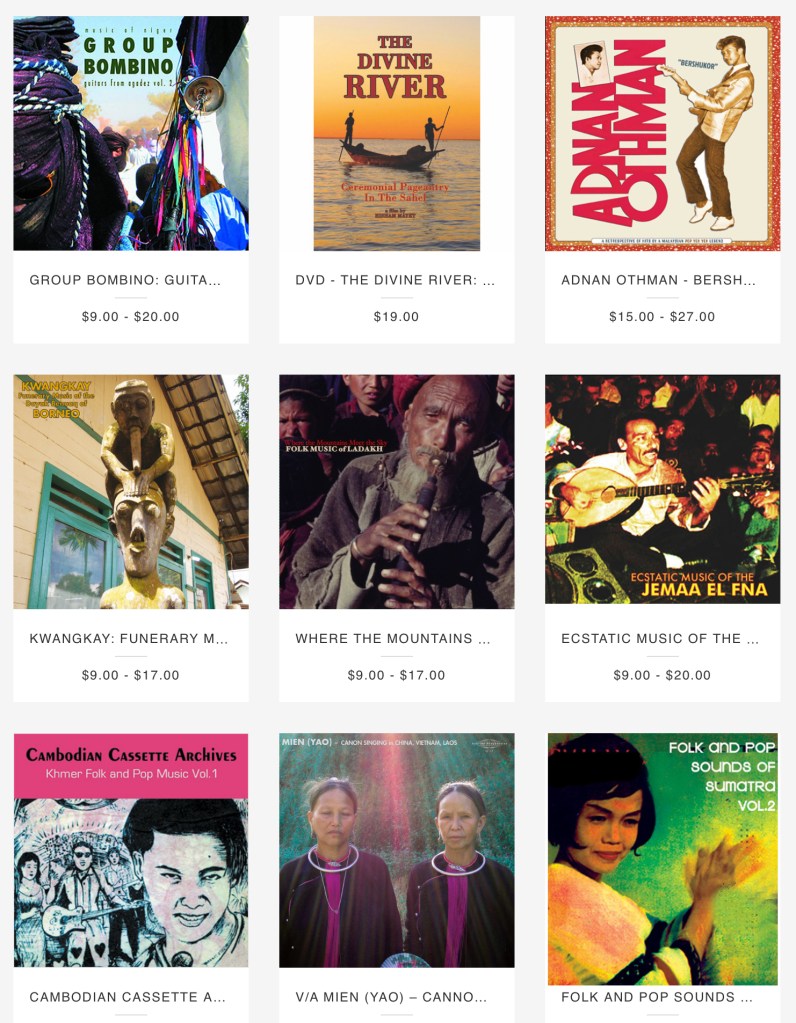

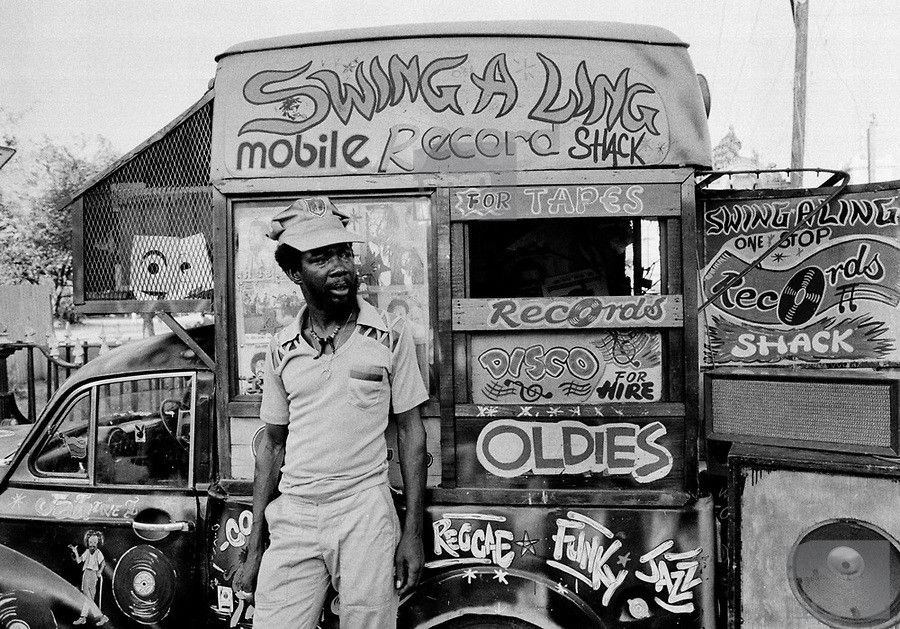

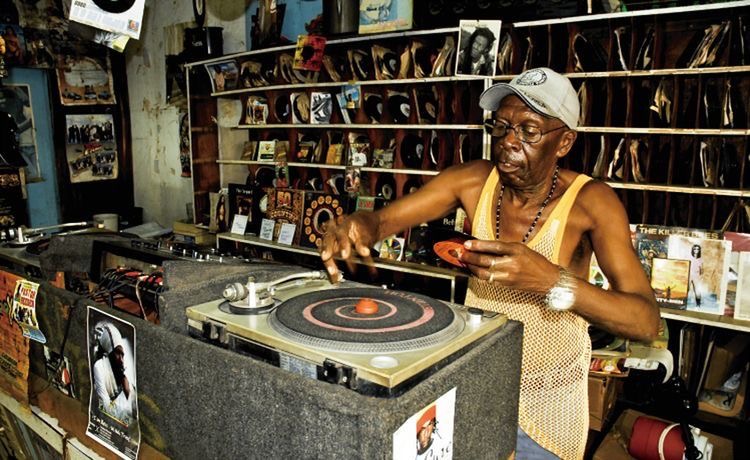

Fast-forward to the 2000s, and enter Sublime Frequencies, a label run by two Lebanese-American brothers with a DIY, post-punk spirit. They didn’t just remix—they archived. Their releases stitched together fragments from local radio, cassette tapes, street recordings, lo-fi broadcasts—a kind of sonic netnography. They were less record producers, more cultural bootleggers in the best sense: ethnomusicologists by instinct rather than degree, scavenging the airwaves for what the mainstream missed.

The same logic seeps into the East. Russia, too, has its own world-music undercurrents. Take Yat-Kha, a Tuvan rock band fronted by Albert Kuvezin, blending throat singing with electric guitars—like if Black Sabbath did ayahuasca in Siberia. Or consider the musicians collecting oral histories and folk sounds from the North Caucasus: not just music, but memory, mapped onto melody. Here too, dual narratives persist: the institutional “castrated” version—think national ensembles like “Sayany” fronted by Sainkho Namtchylak (the most recognized post-Soviet performer in the West)—and the “wild” version: ritualistic, shamanic, ecstatic.

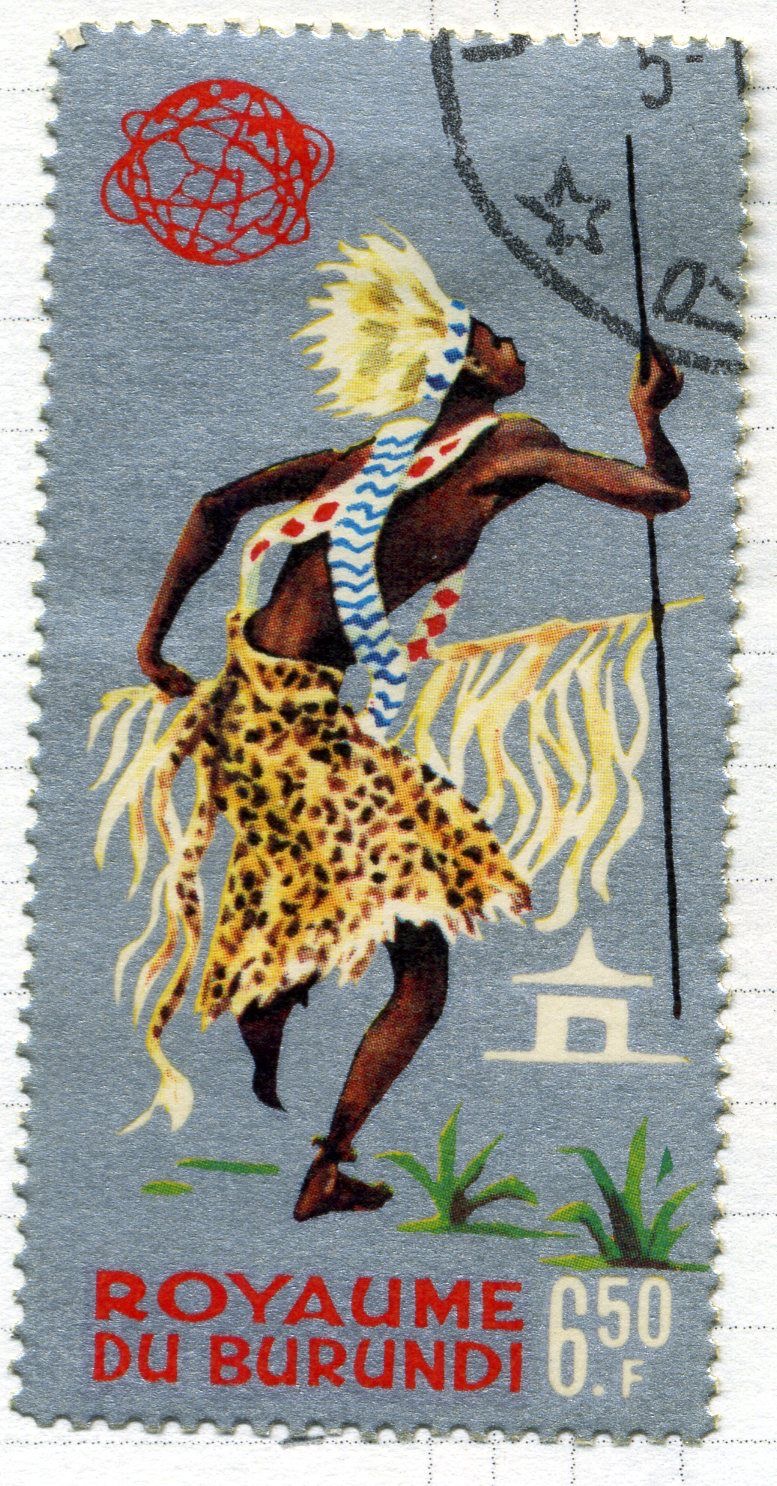

But to truly understand the strange journey of world music into the bloodstream of Western pop, let’s take a detour—to Burundi.

Enter the Drum: How a Field Recording Rewired Pop Culture

In 1967, two French ethnomusicologists recorded the Tambourinaires de Bukirasazi in Burundi. Their raw, hypnotic drumming became the centerpiece of a now-obscure album titled Musique du Burundi (1968). For a decade, it lived in relative obscurity—until someone looped it into a Frankenstein hit.

In 1971, Michel Bernholc released Burundi Black, overdubbing rock instrumentation onto the original field recording. It made the UK Top 40. No credits were given to the original drummers. The West had found its groove, and once again, the beat went on—without royalties.

Cut to the late ’70s: Malcolm McLaren, manager-provocateur of the Sex Pistols, introduced the Burundi Beat to Adam Ant. The result? The drum-heavy, tribal-tinged Kings of the Wild Frontier—a swaggering anthem of post-punk colonial chic that exploded in 1981. Soon, everyone wanted in: Bow Wow Wow, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Peter Gabriel. What The New York Times dubbed “The New Tribalism” was, in essence, a post-punk safari in Doc Martens.

It gets messier. The drummers were never paid. Their work was repackaged, rebranded, and repurposed as raw material for Western cool. And yet—paradox!—the exposure did help launch the Royal Drummers of Burundi as a touring act. Exploitation and elevation, hand in hand. It’s the classic deal: you get fame, we keep the royalties.

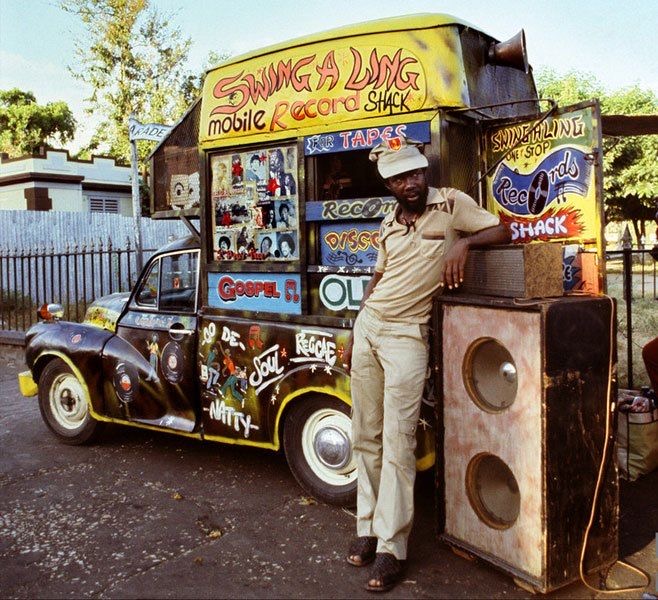

Post-Irony and the World Music 2.0

If the 20th century version of world music was built on romanticism, then the 21st runs on glitch and kitsch. Enter World Music 2.0: ironic, trashy, self-aware. Take Omar Souleyman’s Warni Warni—a viral wedding banger that became an underground electro hit—or Apache Indian’s Chok There, a satirical explosion of cultural mashup and broken dialects. This isn’t about authenticity; it’s about remixing cultural clichés with just enough self-parody to survive globalization with a wink.

Revival and Remix: Tatarka, Ay Yola, and Irina Kairatovna

In 2025, world music continues its post-ironic evolution, riding the edge between cultural pride, viral aesthetics, and digital diaspora. Tatarka—the Tatar rap vlogger-turned-artist Irina Smelaya—hit mainstream consciousness with Altyn, a Tatar-language cloud‑rap single from 2016. Her debut video (shot entirely on a Samsung Galaxy S7) pulled in millions of views and disrupted the Russian scene thanks to its mix of regional identity and Internet-ready flair.

Meanwhile, Bashkir trio Ay Yola—with their mythic‑modern hit Homay—has smashed streaming records across Turkic-speaking regions and climbed high on Shazam and TikTok charts. Set against the epic of Ural‑Batyr, its electronic‑folk fusion resonates across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkey, fueled by a sense of Turkic solidarity and nostalgia for cultural roots.

Not to be overlooked: Kazakh rap acts like Irina Kairatovna blend local dialects, Soviet-era motifs, and trap aesthetics—giving voice to a younger urban generation. That cross‑pollination of tradition and hyphy beats reflects a broader trend: emerging artists from Russian and Central Asian republics are using rap, folk-pop, and mythic storytelling to carve out post‑Soviet identities that are local, digital—and unapologetically hybrid.

World Music 2.0 isn’t world music. It’s world memetics.

“The question is not whether music travels—but how, and at what cost. Who moves it, who claims it, and who is left off the credits?”

Georgina Born

The Reading Room (Unabridged but Unapologetic)

🍬 Connell & Gibson — On how “locality” is manufactured, how “authenticity” is a performance, and how the label industry thrives on curating exoticism like a Spotify playlist for the colonial subconscious.

🍬 David Novak in Punk Ethnography — A deep dive into the ethos and ethics of Sublime Frequencies: DIY ethnography or just another form of neo-sampling?

🍬 Thomas Burkhalter in The Arab Avant-Garde — On the Western reception of contemporary Arab music and the trap of “listening progressively” while still gazing exotically.

🍬 S. Polyakov et al. — On Tatar rap in post-Soviet Kazan. Yes, Kazan is spitting bars now—and it’s more postcolonial than you think.

🍬 A. Wenzel et al. — On the intersection of Yakut identity, independent hip-hop, and urbanization in Russia’s Far East. (Spoiler: Yakut cinema isn’t the only thing booming.)

So where does that leave us?

Maybe with the uncomfortable truth that appropriation and inspiration often share the same rhythm. That every beat you borrow carries a ghost. And that the world—musical or otherwise—was never meant to be easy listening.

Stay tuned, stay suspicious. The next global sound may already be playing on someone else’s radio.

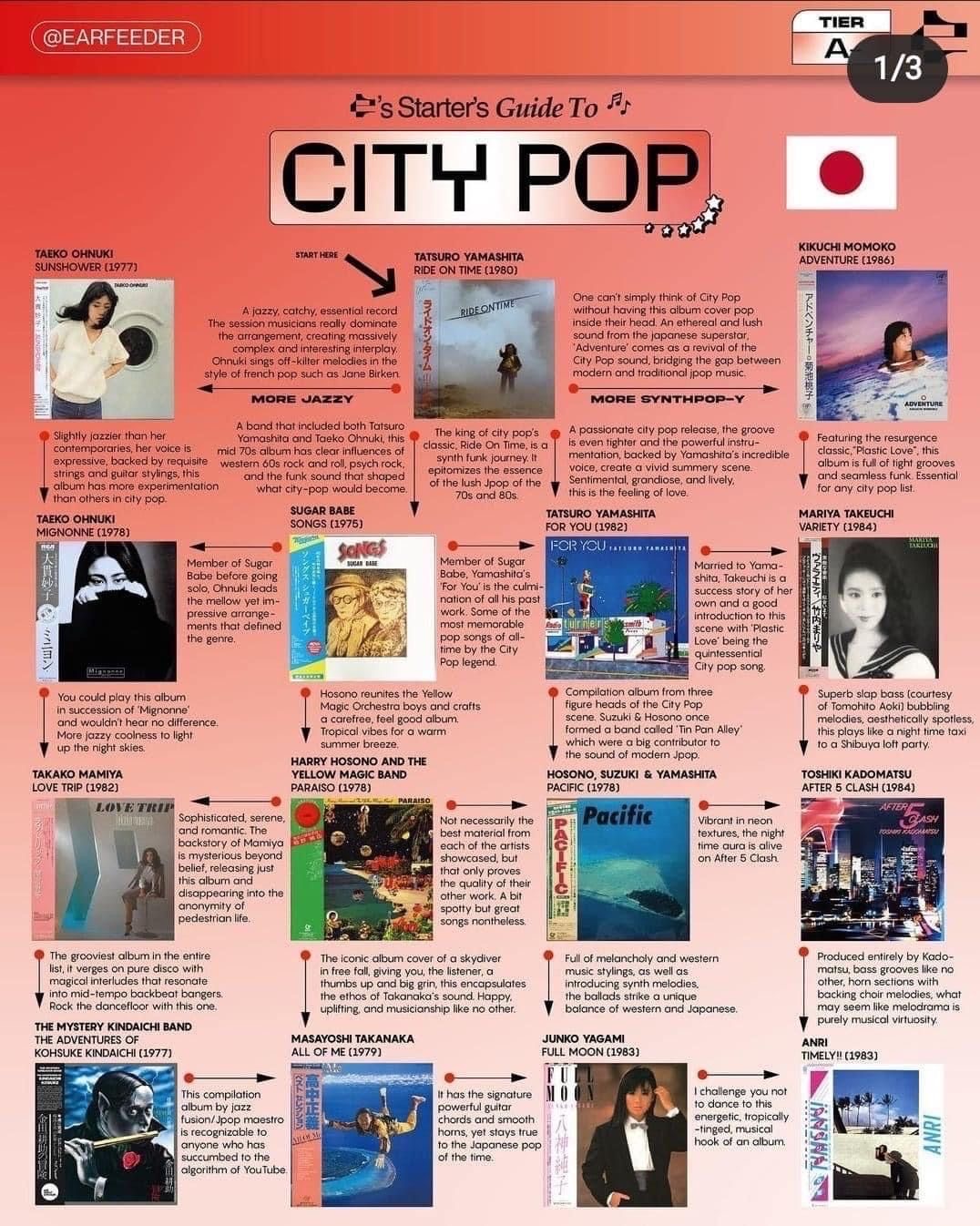

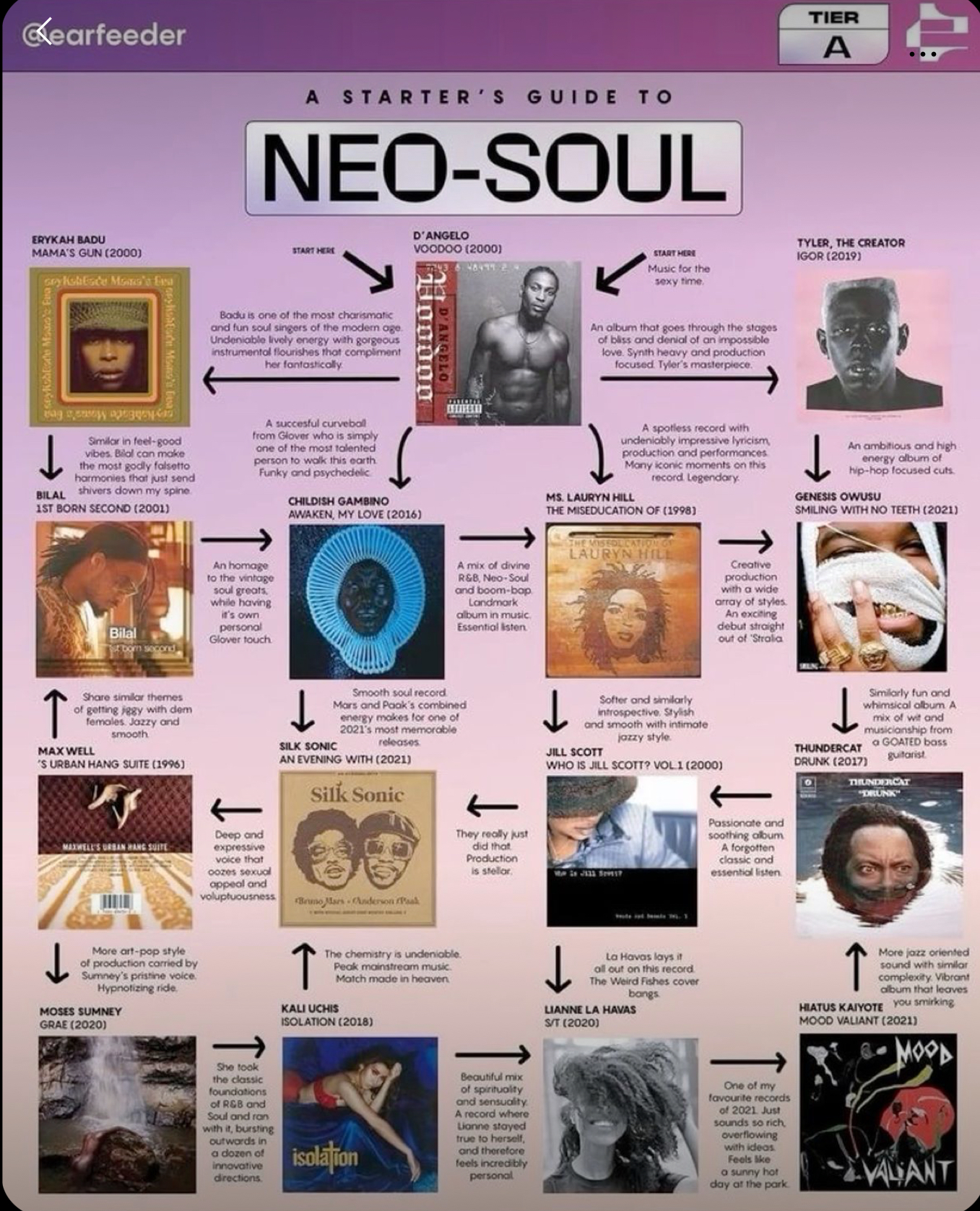

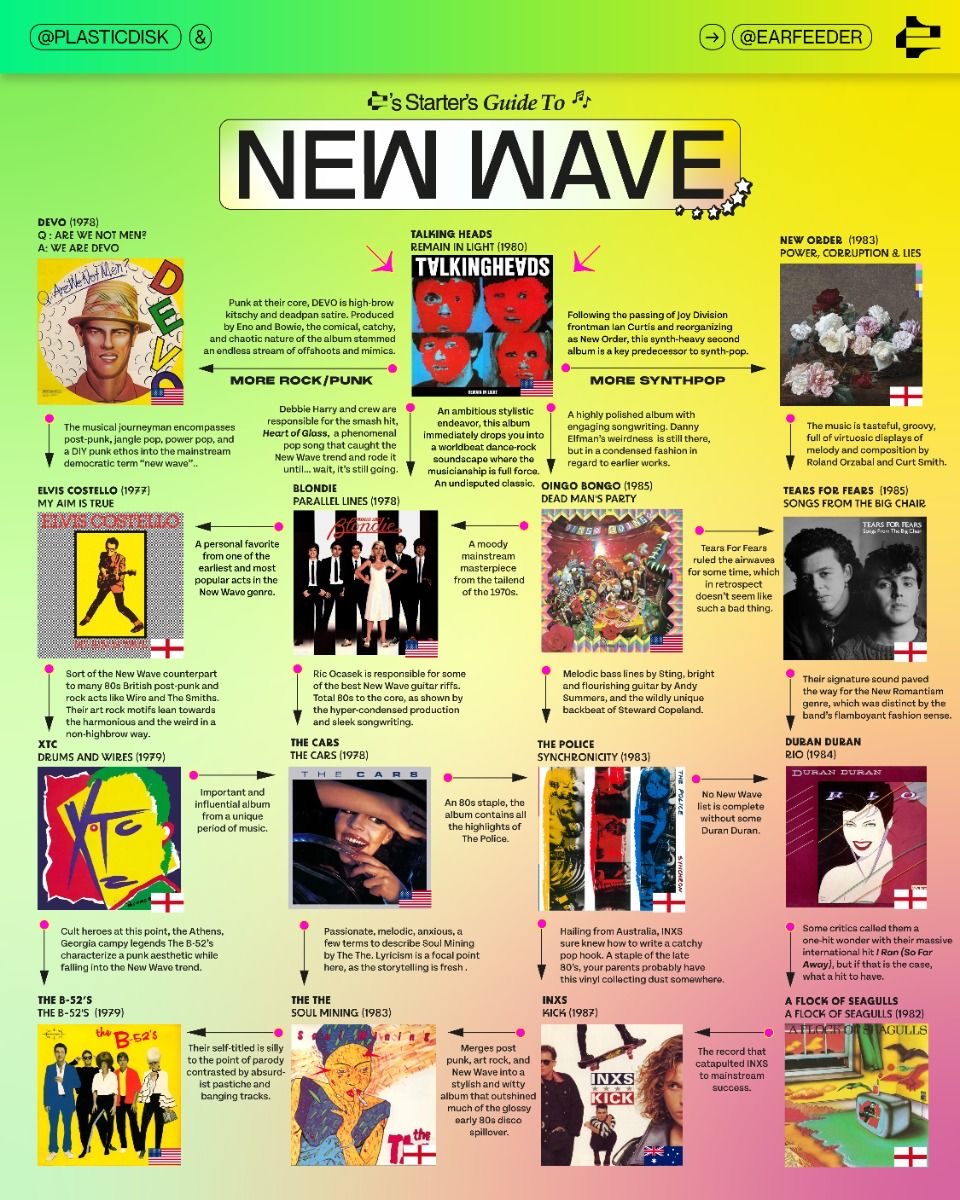

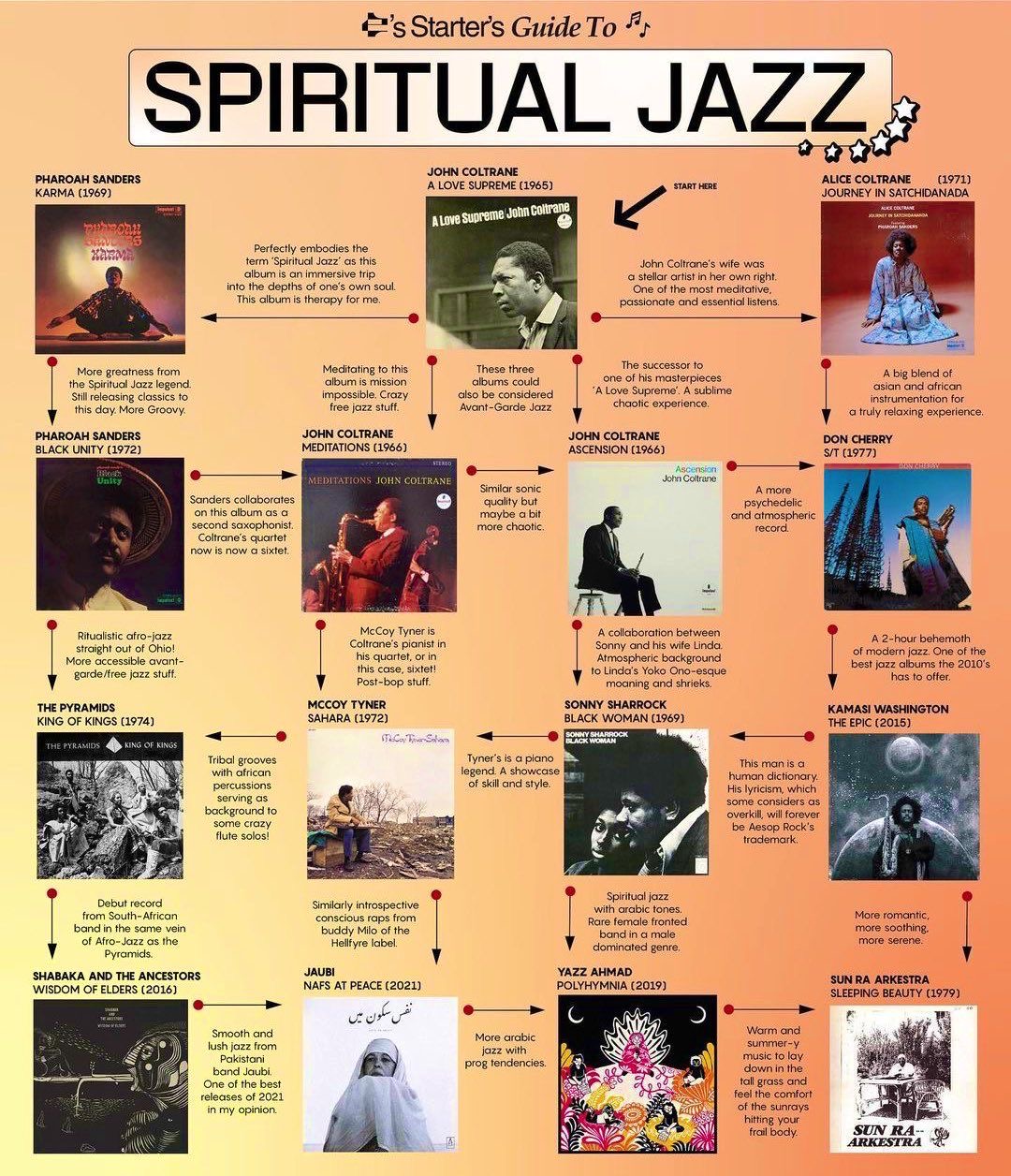

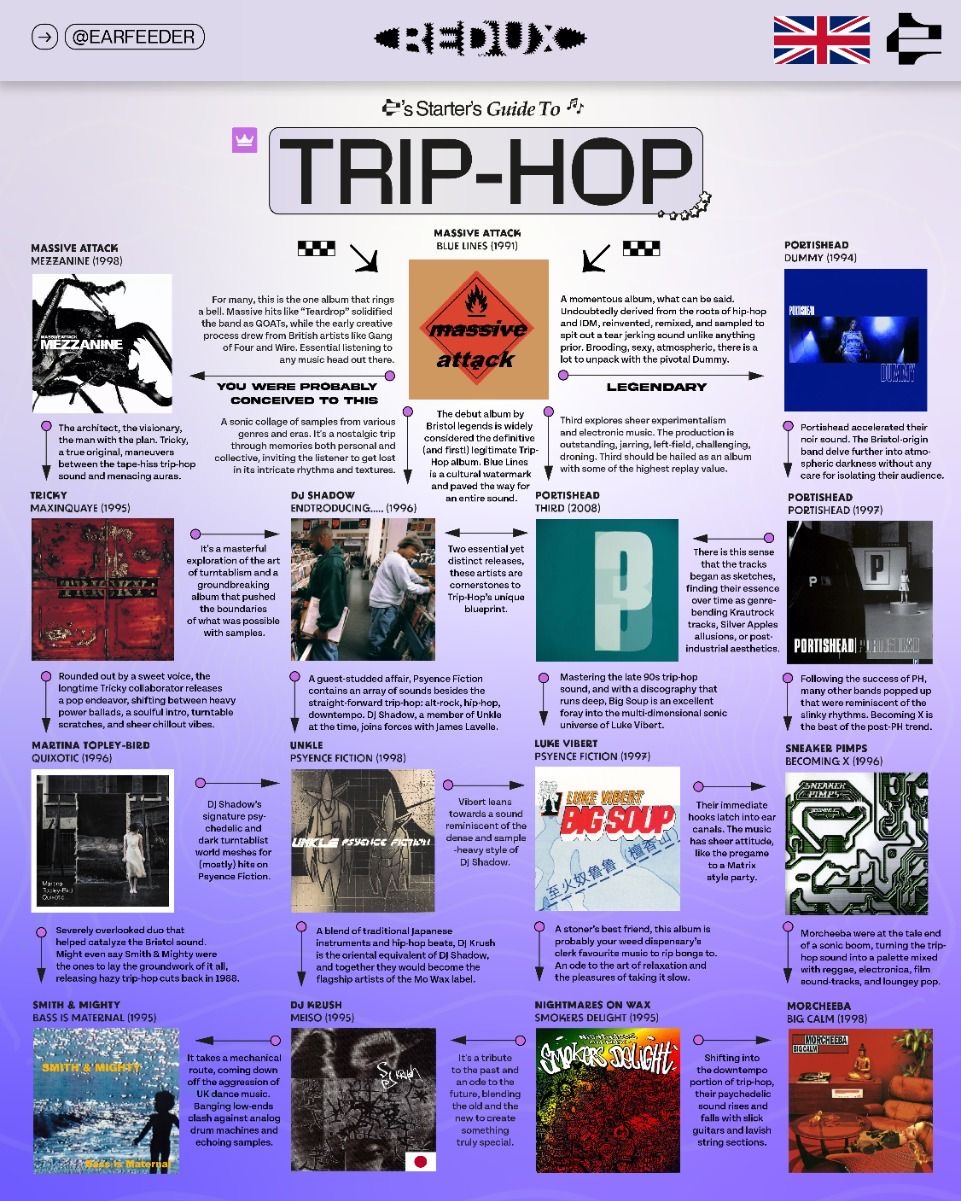

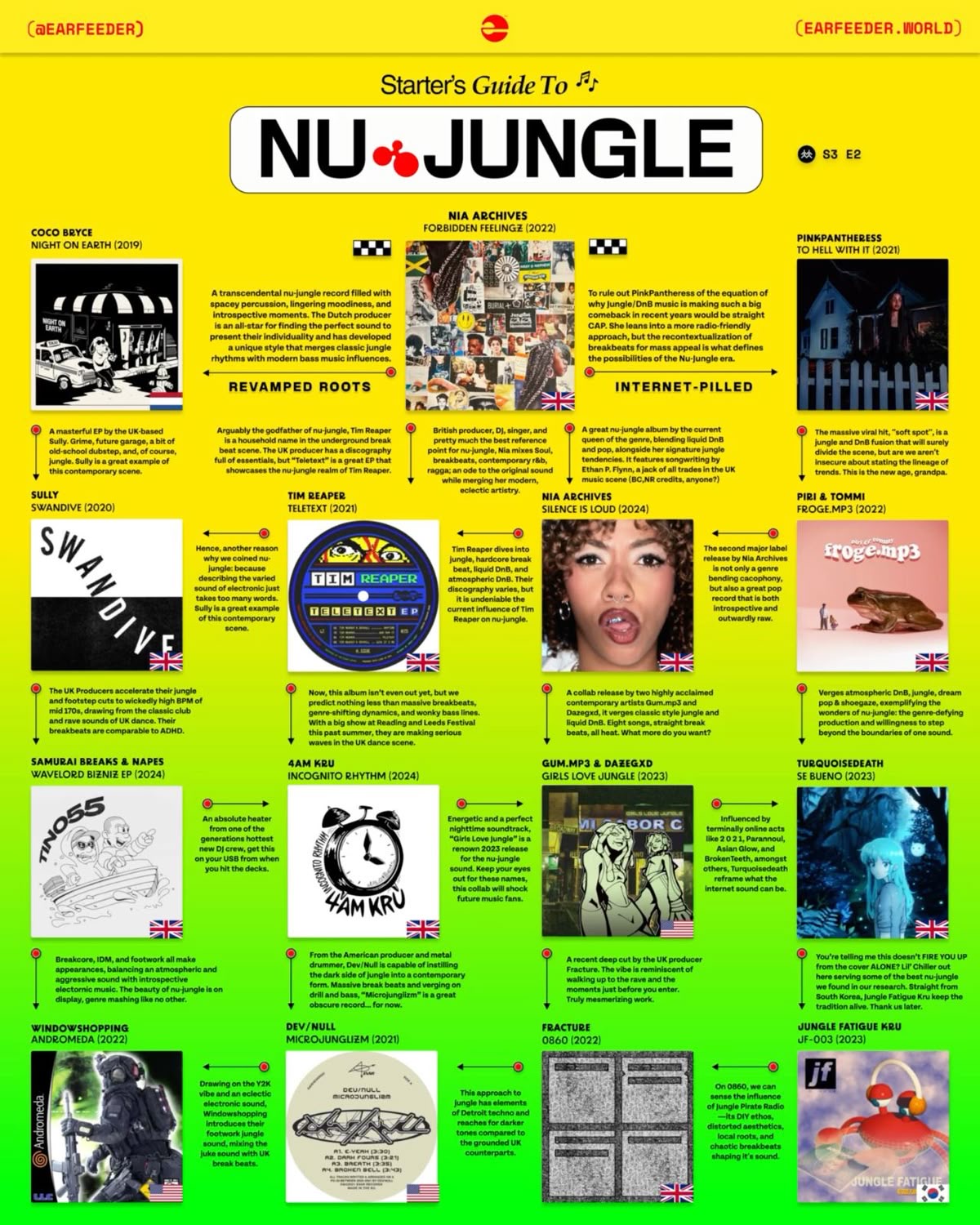

Bonus: A EarFeeder’s Starter’s Guide to the music genres that deserve to get more ears — and here are some of my personal faves:

Sign up for our freshly baked posts

Get the latest culture, movie, and urban life updates sent to your inbox.

Subscribe

Join a bunch of happy subscribers!

You must be logged in to post a comment.