What do folk, pop and post-punk have in common?

Not much, really! But there’s a point behind the clickbait title: at different moments all these genres went through what you could call a “renaissance,” or what music historians like to label a revival.

The funny thing is, these revivals weren’t usually born from some mass nostalgia for a lost era. More often they were engineered vertically, in a very deliberate way. Case in point: the first American folk revival during the New Deal. Roosevelt’s cultural policy collided with the Dust Bowl migrations and the Great Depression.

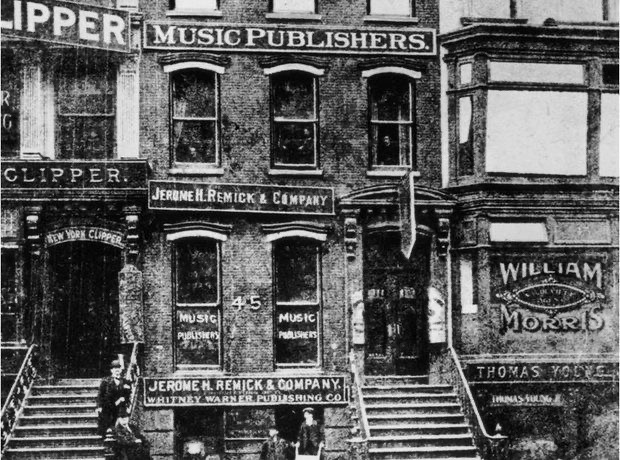

In the 1930s, folk wasn’t a kitschy coffeehouse genre but a communication tool for the working class—a kind of oppositional culture set against the mass-market polish of Tin Pan Alley.

Roosevelt clocked this and basically went: “real America” is slipping away (Trump didn’t invent that line of thinking, he just rebranded it). Rural-patriarchal Southern culture was being crushed under urbanization.

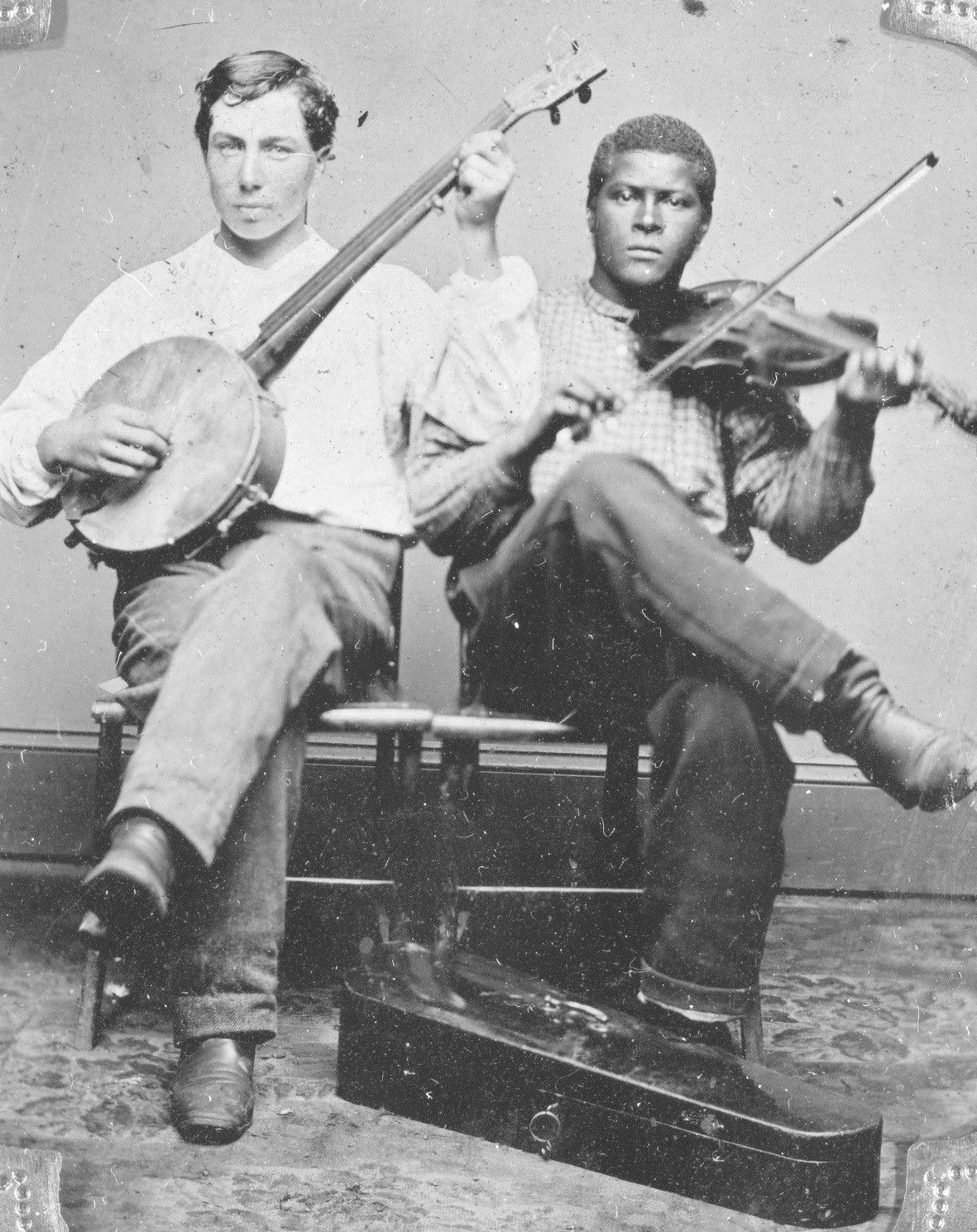

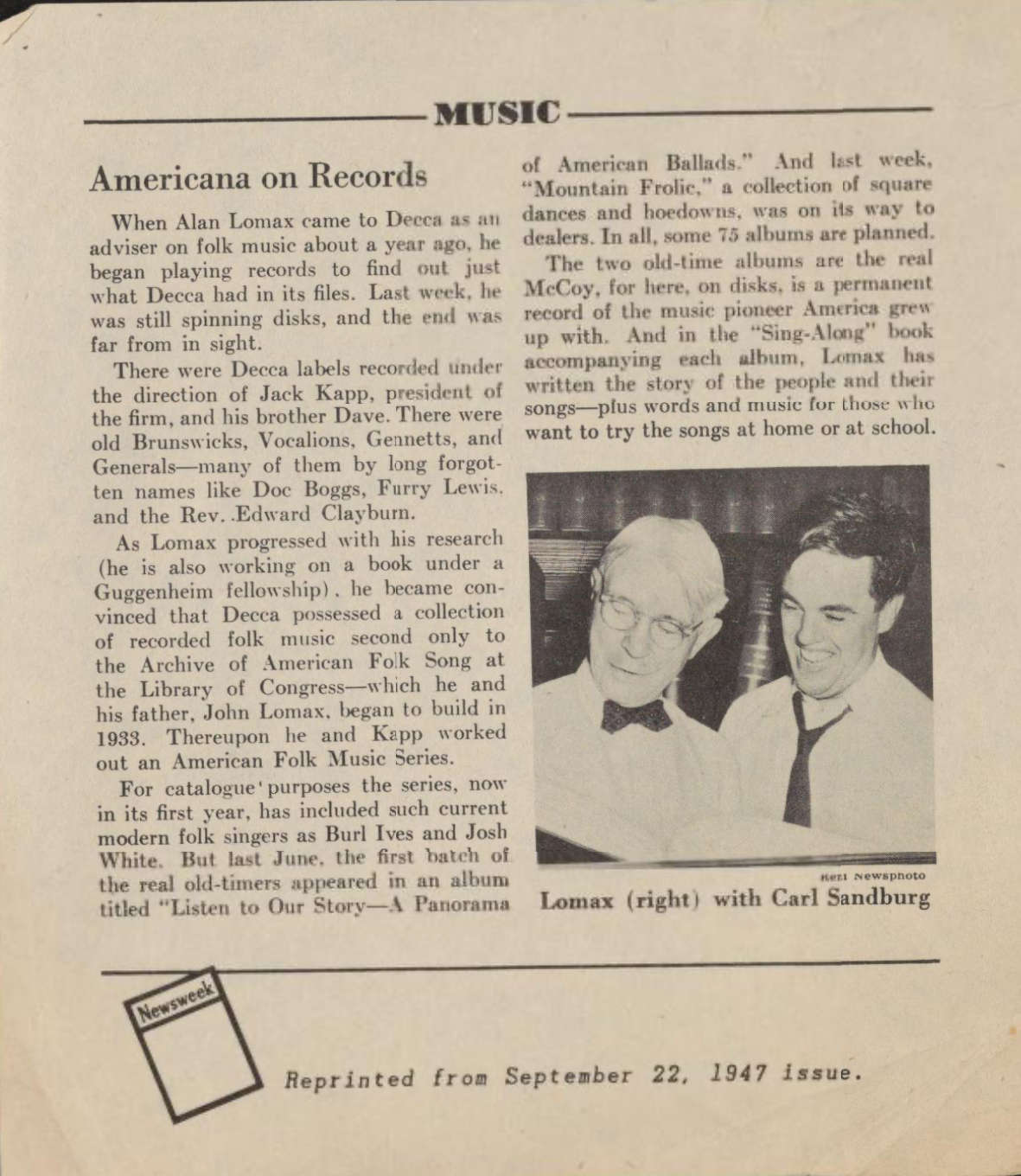

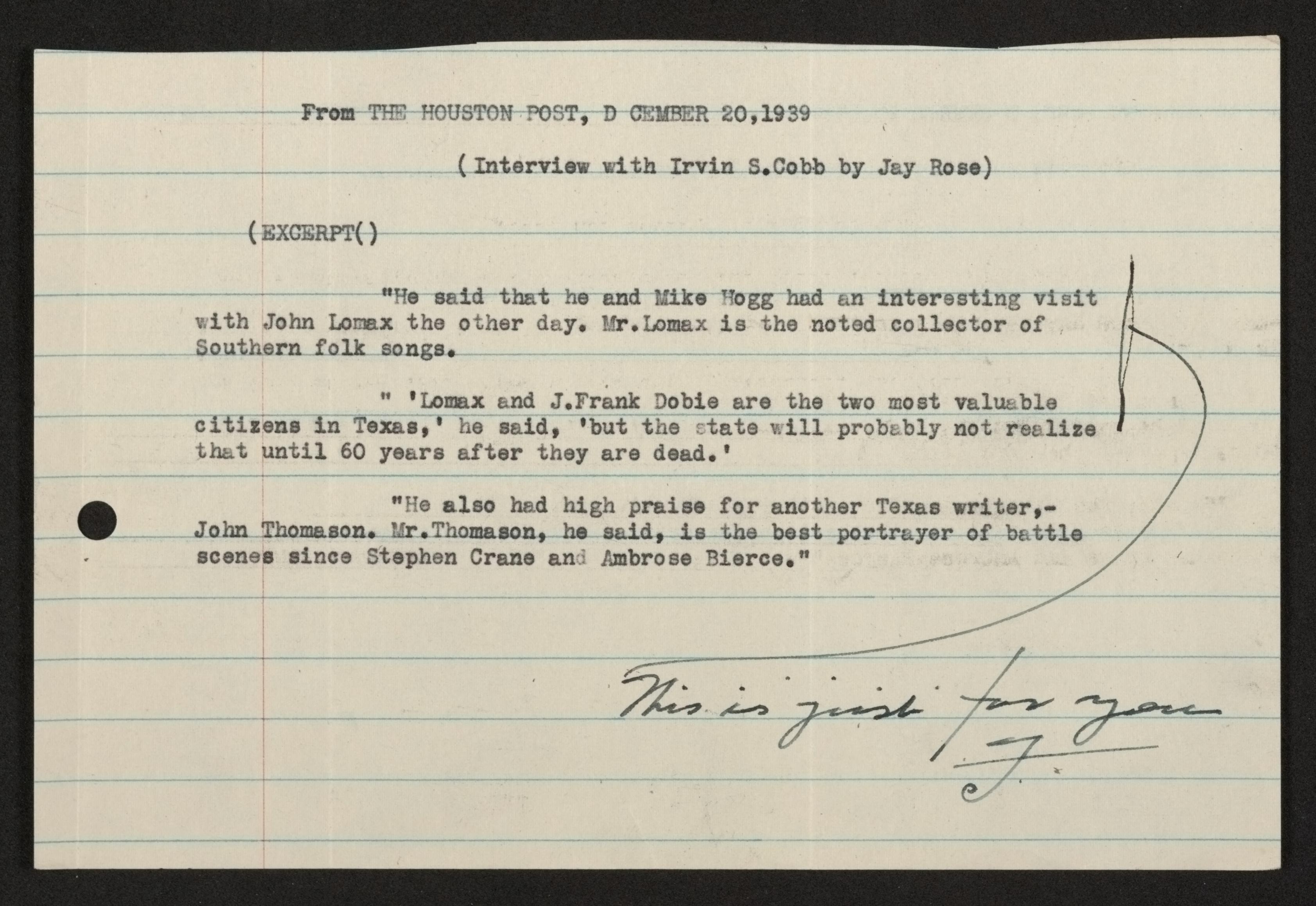

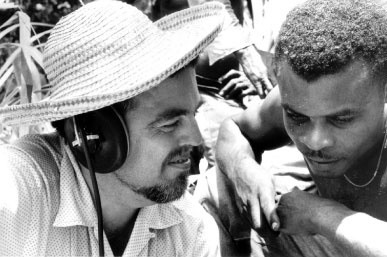

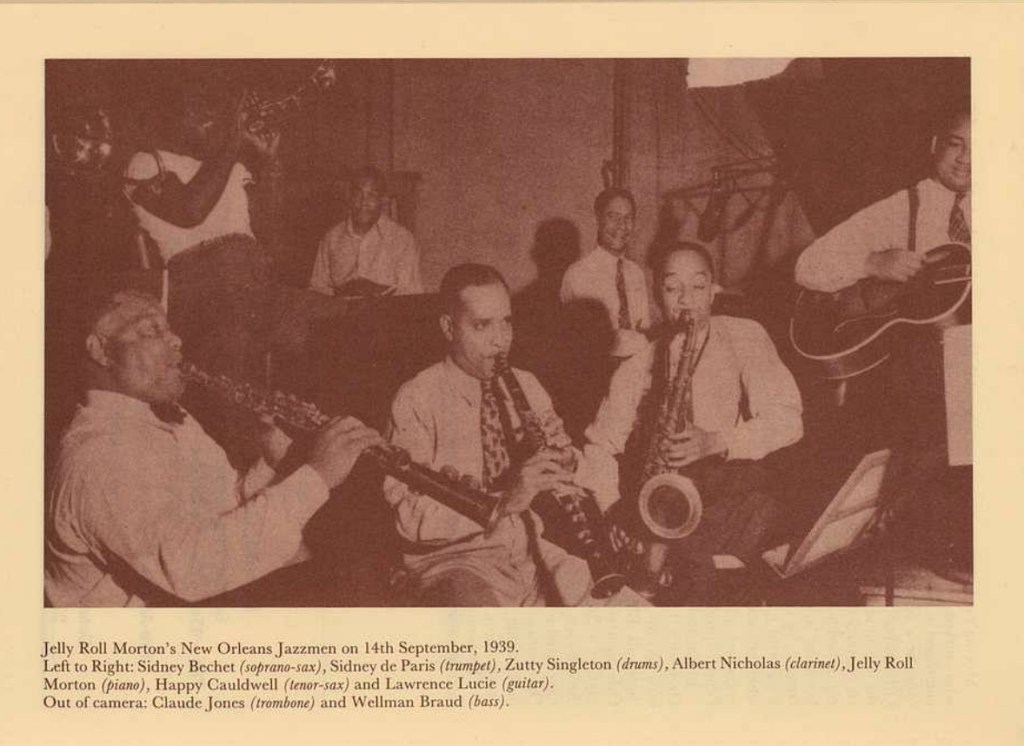

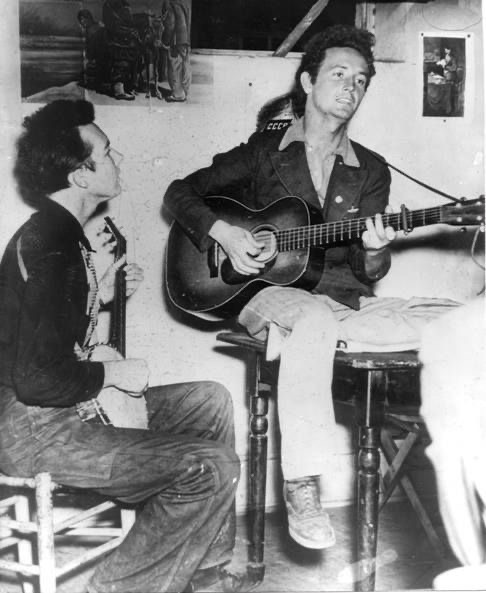

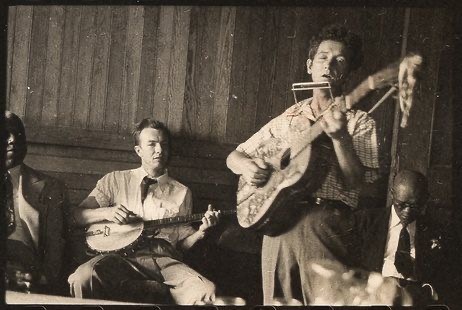

Which meant it was time to craft a cultural policy that could absorb all those “roots” and repurpose them for national unity. In other words: a state project. Meet the Blues Brothers Alan and John Lomax, running around the American South with field recorders, documenting local ballads, prison work songs, and back-porch hymns.

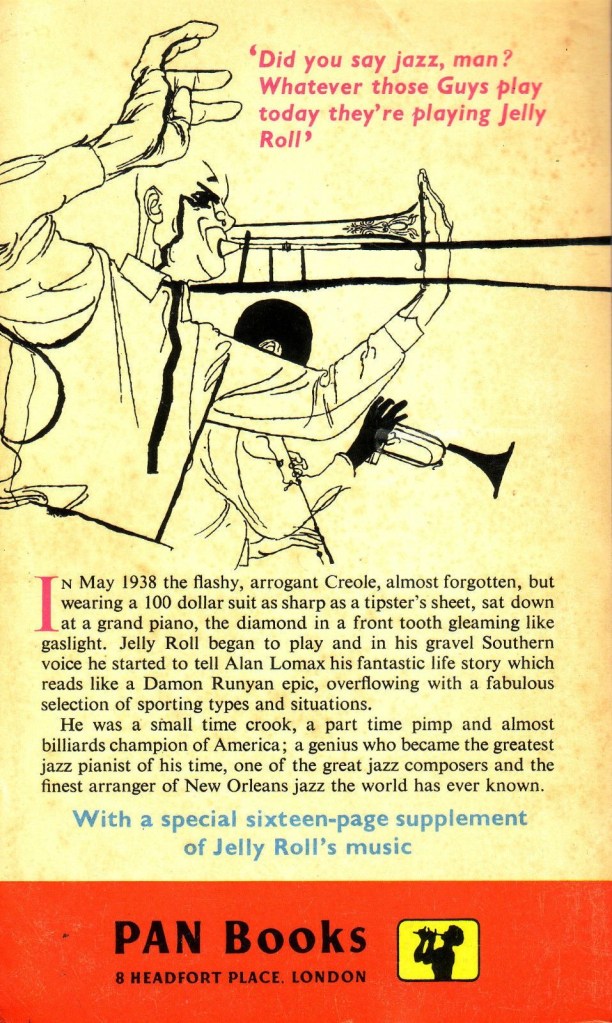

Alan Lomax — “Mister Jelly Roll”, back cover, Pan Books, London (1959), Illustrations by David Stone Martin.

Of course, what started as ethnography was quickly commodified. The second wave of folk revival hit in the 1950s–60s, now fully mainstream: folk supergroups, Bob Dylan, the mass industry Adorno warned us about, even a layer of commercialized leftism. And somewhere in between, figures like Pete Seeger acted as living bridges between the archive and the stage. Seeger wasn’t just performing folk; he was recording and collecting it, moving through the same backroads as the Lomaxes. His presence—even fictionalized later in films like Complete Unknown—is a reminder that revival wasn’t born in studios but in a messy network of voices, tape reels, and borrowed songs.

And on the other side of the Atlantic?

As Dale Carter argues in “A Bridge Too Far? Cosmopolitanism and the Anglo‑American Folk Revival, 1945–1965”, the British revival took shape amid imperial decay. Postcolonial anxiety merged with a craving for “locality.” As the colonies dissolved, Britain turned inward—to coal miners’ ballads, Celtic motifs, and Welsh choirs. Carter frames the Lomax tapes not merely as preserved artifacts, but as blueprints: a sonic strategy for reassembling a beleaguered national identity from the ground up .

In Carter’s reading, the revival functioned like cultural therapy—a mirror held up to a fading empire. Britain hearing American prison songs wasn’t passive consumption—it was a cultural diagnosis. The Lomaxes’ injections arrived just as Ewan MacColl, A. L. Lloyd, and Peggy Seeger were actively constructing a folk canon from oral traditions. Alan Lomax later edited The Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music in London. This British revival was collaborative, networked, and deeply transatlantic.

Then comes Joe Boyd with his memoir White Bicycles—Making Music in the 1960s, which situates the revival within ’60s London’s cultural swirl. Boyd—producer for Fairport Convention, Incredible String Band, Nick Drake—tells how British folk’s archival aesthetic bled into the psychedelic underground. At the UFO Club (which Boyd co-founded), audiences absorbed Appalachian ballads alongside Pink Floyd and Soft Machine. He shows how folk recordings invited experimental reinterpretation, helping birth acid folk—a musical genre that fused archival roots with reverberation, exotic instrumentation, and psychedelic ambition.

Boyd reflects on nostalgia and innovation as inseparable:

“History today seems more like a postmodern collage; we are surrounded by two‑dimensional representations of our heritage.”

That quote really nails it: an archive doesn’t merely preserve—it constructs. What the Lomaxes recorded as raw folklore became “authentic” in post-imperial Britain, then layered into aesthetic in Boyd’s era. By the time those voices surfaced in Fairport’s Liege & Lief or the Incredible String Band’s improvisations, the chain-gang songs had transformed into myths—and myth into marketable music.

Postscript: from folk to post-punk

You can trace that line further. The same mechanics of archival “roots” repackaging reappear in the late ’70s–’80s post-punk scene: Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Pogues, even the Burundi Beat phenomenon. These aren’t simple nostalgia loops; they’re ways of re-engineering identity at moments of cultural crisis—national, musical, personal.

Stay tuned. The next revival is already being stored somewhere in the post-human cloud.

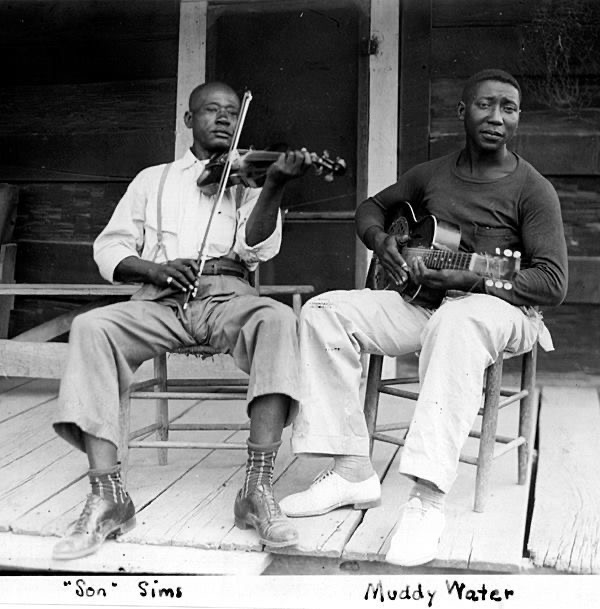

R.L. Burnside at home in Independence, Mississippi, shot by Alan Lomax, Worth Long, and John Bishop in August, 1978.

Sign up for our freshly baked posts

Get the latest culture, movie, and urban life updates sent to your inbox.

Subscribe

Join a bunch of happy subscribers!

You must be logged in to post a comment.